Up In the Air 26 January 2014

2014 marks a decade since since Google acquired Keyhole Corporation, a Silicon Valley start-up whose mapping technology transformed the way we see the world. Keyhole created the seamless combination of high-resolution satellite and aerial imagery that provides the geo-located guts of Google Earth and Google Maps, the satellite view that has become a ubiquitous part of our digital lives.

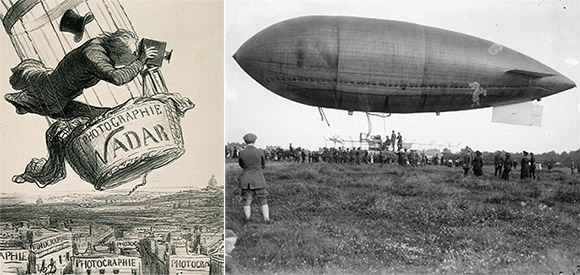

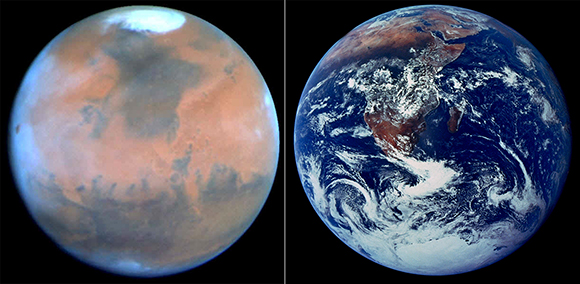

As a descriptor, satellite is sexier than aerial, conjuring Sputnik and the space age instead of the drifting balloons and lumbering dirigibles in which photography first took flight. Somehow, the view from space has managed to retain its romance. But then I was one of those kids in the 70s who wrote to NASA for views of space–photographs of Mars sent back by the Viking orbiter.

They arrived in a big manilla envelope stiff with cardboard and emblazoned with NASA’s brand new logo. Richard Danne and Bruce Blackburn designed the so-called worm to replace the Administration’s original meatball logo (to which it returned in 1992). With its sleek continuous letterforms and missing cross strokes, the NASA worm looked absolutely like the future to me–and so did the pictures inside the envelope.

Today, we spend more time engaged in the planetary equivalent of navel-gazing. It’s not the red planet that captures our imagination; it’s our own “big blue marble,” a preoccupation that also dates to the 70s, when Apollo 17 astronauts sent back the now iconic view of the illuminated face of the earth. If photo #AS17-148-22727 gave us a sense of the earth’s wholeness (as in Whole Earth, which used a comparable 1967 view on the cover of its first catalog), it was Charles and Ray Eames who provided a sequential point of view.

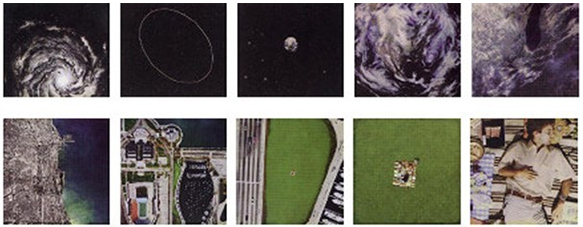

In 1968, the Commission on College Physics (which promoted physics education during the space race) asked the Eameses to make a film to explain exponents. Their famous response used Kees Boeke’s Cosmic View: The Universe in 40 Jumps as the starting point for a dramatic human-scaled visualization of moving through space by Powers of Ten. In the revised and expanded version of 1977 (which my elementary school screened in an assembly), it takes just over a minute to move out from a couple picnicking on a lawn near Lake Michigan to the whole earth view of 10,000,000 meters (10 to the 7th power).

What was mind-blowing then, we take for granted now. Even though the jumps are not as regular as in Powers of Ten (in Google imagery they shift back and forth between meters and feet, kilometers and miles), with a few mouse clicks, we easily apprehend how different Chicago’s Burnham Park looks today.

In 1977, the couple picnicked on a flat expanse of lawn hard by the northbound lanes of Lake Shore Drive and the parking lots of Soldier Field. In 2014, they would spread their blanket in a picturesque landscape of grassy berms, walking paths, trees and a winding roadway–the results of a 1996 road relocation and a 2003 renovation of the stadium (the one that resulted in its de-listing from the National Register). Attempting to show us “the relative size of things in the universe” and “the effect of adding another zero,” the Eameses anticipated a crucial aspect of contemporary visuality.

We zoom in, we zoom out; we locate ourselves with geospatial precision. We encounter bytes of biography: the Street View of my block of the Upper West Side captures one of those rare days when my very own car was parked outside of my very own building. We spot details that produce a frisson of familiarity: the outline of the Central Park reservoir, the shadow of an oversized winged “radiator cap” on the 31st floor of the Chrysler building.

Mostly, though, we click and drag with detachment; blame it on digital mediation or, less virtually, on the routine nature of the aerial view in a world of $99 round trips. But even in the 21st century, in between the flat screen at hand and the pressurized cabin at 30,000 feet, we can still find moments of visceral visual experience, of emotional resonance and maybe even joy–as I discovered when I climbed aboard an Airbus Eurocopter AStar 350 for a 30 minute ride.

My companions had hoped for a Sikorsky (departing from the Westchester County Airport, we were very nearly in the Black Hawk‘s home territory of southern Connecticut), but I had no preference, my ignorance of helicopters trumping my customary localism. As it applies to metropolitan development and centralized urbanization, localism wasn’t so much trumped that morning, as radically intensified.

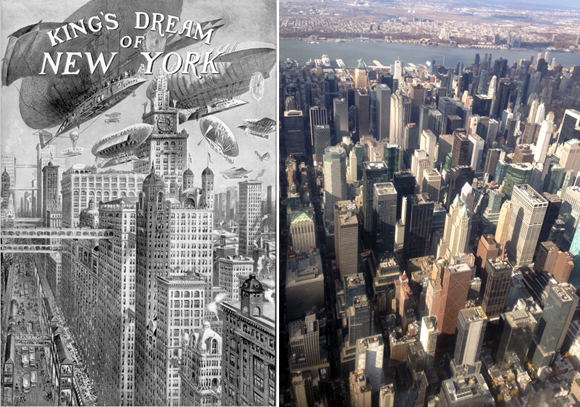

Flying from White Plains to Midtown, we knew what to expect: low rise giving way to high-rise, greenfield to asphalt, open space to density, suburb to city. Even if we didn’t reside in Greater New York, even if we’d never been to the Panorama in Flushing Meadow, this particular urban morphology belongs to the collective memory of the 20th century. We knew it instinctively, even before the helicopter left the ground.

But there it was, the periphery giving way to the center with startling clarity and autumnal color (it was mid-November) at somewhere around 1500 feet. If the birds-eye perspective does little to improve the view of McMansion subdivisions, it gives even undistinguished corporate and college groundscrapers an aura of geometric abstraction.

Structures already possessing geometric abstraction–like the Breuers in the Bronx (originally NYU/now Bronx Community College)–appear even more potently sculptural. Even the Cross Bronx Expressway, when seen from above, looks less “hacked with a meat axe” (as Marshall Berman memorably described it), the graceful curves of its interchanges almost convincing us that it is not the ring of hell we know it to be from behind the wheel.

We followed the East River until we could see the towers clustering at the lower edge of Central Park, and then we turned toward the middle of the island. Looking south, you could see the skyscrapers giving way to mid-rise blocks of the 20s and 30s, where, according to tradition, the Manhattan schist is too far below the surface to support tall buildings (recent research has rendered this more urban legend than geological fact).

Between the thumping of the chopper blades, felt bodily, and the isolation of the headsets, experienced aurally, we hovered above midtown in a warp of dislocation. And yet we were absolutely in the city, maybe even of the city–if we accept verticality as urban essence. Flying in that helicopter was like a shot of hyper-reality (in a simple literal sense, rather than Baudrillard’s), the urban condition as adrenaline, imagined, actualized and exaggerated.

If the city I witnessed and photographed from the helicopter is nearly identical to the one captured in images accessible on Google 24/7, there’s one critical difference: looking at midtown on Google Maps or Google Earth has never made me weep.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.