Sheepish 1 November 2013

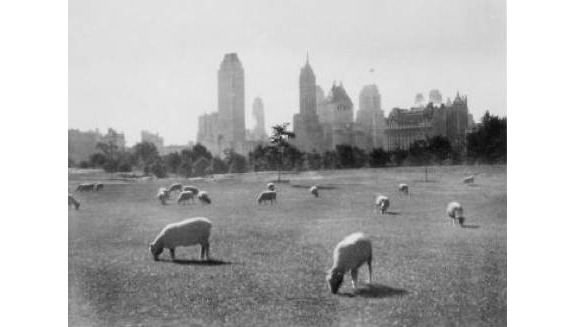

In 1934 Robert Moses kicked the sheep out of Central Park to make room for Tavern on the Green. Though the New York Times applauded their contribution to park maintenance–the flock kept the meadow trimmed and fertilized for more than half a century–Moses claimed the 49 purebred Dorsets were deformed from inbreeding, so he sent them packing to Brooklyn, where they were kept in line by two Scotch collies who worked the pastures in Prospect Park.

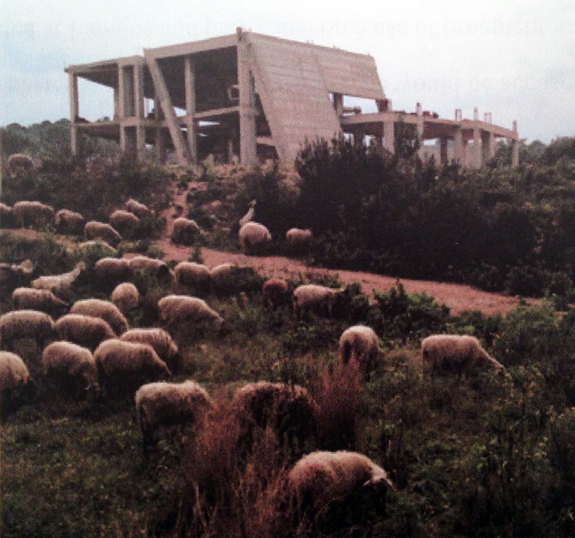

They don’t look particularly deformed here, and it’s hard to imagine anyone who encountered them in 1930, when this photograph was taken, being concerned about genetic mutations while contemplating such a lovely contrast of pastoralism and urbanism. But then I’m partial to this sort of juxtaposition.

I live happily with Eva Sauer’s Rohbauten 03, which combines the high-key naturalism of William Holman Hunt and the Pre-Raphaelites (note the grazing sheep) with the sober objectivity of Bernd and Hilla Becher (note the concrete structure). Though the work has definite end-of-empire overtones, it seems to depict occupation more than abandonment.

That same effect, though with a large measure of surreal sweetness, lingers about Sheep Station, an installation by the late François-Xavier Lalanne in a former gas station in Chelsea. Lahanne built a four decade career on “les Moutons,” epoxy stone and bronze ovine sculptures that supposedly “demystify art and capture its joie de vivre.” It’s not clear how much demystifying is taking place on the corner of West 24th and 10th, but there is something quietly joyful, or maybe just goofy, about 25 cast sheep standing under the canopy of what was, until quite recently, a functioning filling station.

Corralled by white horse fencing and rows of junipers, the sheep stand about on artificial berms and a rolling lawn covered in real turf. They cozy up to the ice machine; they huddle around the pumps, as if waiting for their tanks to fill. Except there aren’t any cars, because the gas station is now a sheep station, get it?

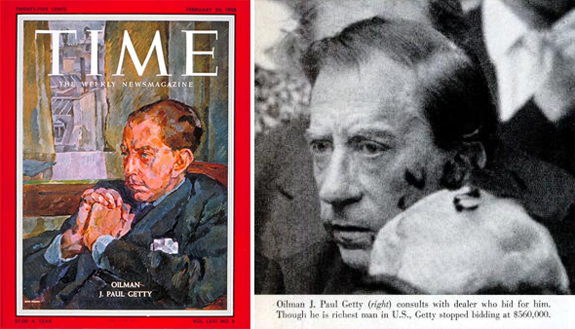

And the sheep station is an art station–Sheep Station at Getty Station, get it? So much self-satsified word play distracts us from larger narratives that are worth considering–about oil and art and art and real estate and real estate and oil.

There’s nothing ironic about conjoining Getty and art since, after all, the world’s richest museum was established by an oil man. But the gas station that is now the Getty Station severed its ties to J. Paul’s original, eponymous company some years back.

Getty Oil organized a realty division in the early 70s to handle all property transactions related to its retail outlets and distribution terminals. This division remained part of the company that Texaco took over in the mid-80s, in one of the ugliest deals of a decade rife with notorious mergers and acquisitions. But during yet another takeover in 2000, when what remained of post-Texaco Getty was acquired by the Russian giant Lukoil, Getty Realty Corporation was spun off as an independent REIT responsible for around 1300 gas stations nationwide. Getty Realty promptly leased many of these stations back to Lukoil, which began rebranding them as part of its global chain.

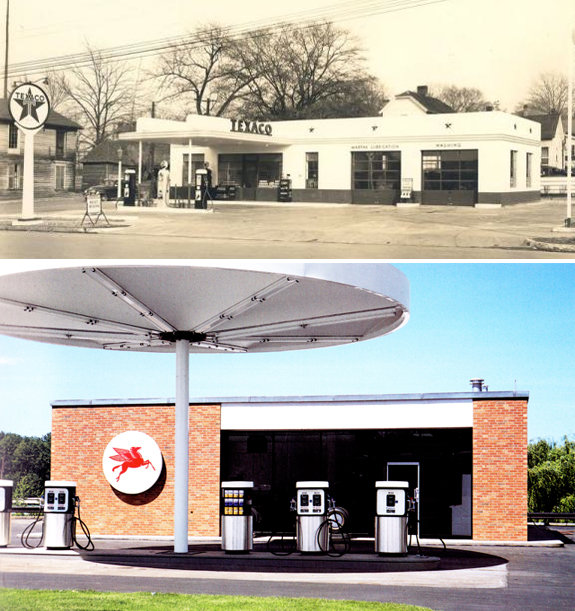

On 24th and 10th, that meant an over-sized canopy with a distinctive K-profile and a red and white color scheme on the canopy, pumps, double-height free standing sign, and small CMU box housing a convenience store. This was hardly gas station retail design at its most heroic–nothing close to Walter Dorwin Teague’s work for Texaco in the 30s and 40s or Eliot Noyes’ and Chermayeff and Geismar’s work for Mobil in the 60s and 70s.

Instead, the Lukoil conversions offered only modest examples of what John Jakle and Keith Sculle call the place-product-packaging that was critical to the acceptance of the automotive service station as a ubiquitous feature of the American landscape in the 20th century. Lukoil’s lack of inspirational design is hardly surprising: in a New York Times article on the 2000 deal, an oil industry analyst observed that “these aren’t the nicest gas stations,” speculating that the company’s real motive was to burnish its reputation by acquiring (and then effacing) an American brand.

But Getty technically still owned these Lukoil gas stations, even though, with each passing year, it seemed to look at them more and more as real estate. With both oil prices and property prices at all time highs in the past decade, Getty began to evaluate its portfolio from a different perspective. When oil prices are high, it’s tough to make a profit selling gas (even with a convenience store attached); when property prices are high it’s easy to make a profit selling property, especially when those properties are in some of the hottest real estate markets in the country.

In the first six months of 2013, Getty Realty Corporation sold 77 of its properties, including the gas station on 24th and 10th, which developer Michael Shvo purchased for $23.5 million with plans to turn the site into “the premier collection of luxury residences near the High Line.” When luxury condos became collections is the subject for another post; in the meantime, the newly rebranded Getty Station serves as an exhibition space. Cue the sheep.

It’s easy to grumble that yet another high-end condo will inevitably push the art out of Chelsea, exactly the way the high-end retail pushed the art out of SoHo, which is what caused the art to decamp to Chelsea in the first place–beginning with the Matthew Marks Gallery nearly 20 years ago. We all know how this works: the industry leaves, the artists move in, the dealers follow; the art lovers come to look at the art, the fashionistas arrive to attend the parties, the developers follow, jacking up the prices and causing the whole thing to start over somewhere else. We also know that in the 21st century how this works has gotten a whole lot more complicated. In Chelsea, for example, those complications include the redevelopment of the High Line into a tourist-jammed park, the rezoning of the neighborhood’s west side to encourage residential high-rises, and the coming-in-2015 institutional presence of the Whitney Museum, which is technically in the Meatpacking District, but feeds off, and contributes to, the area’s identity as contemporary art central.

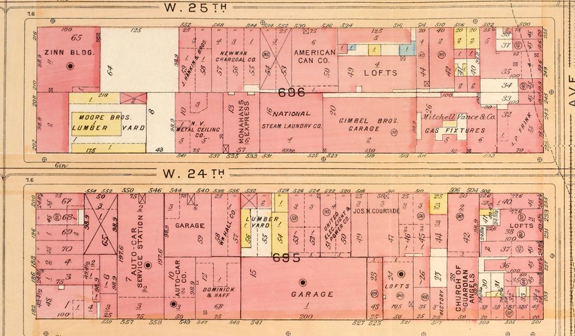

Another complicating factor is that a certain sector of the industry never quite left, at least not until the art people and especially the real estate people forced it out. (Historical note: picking up my ancient Honda after having the interior steam-cleaned in the West 20s early in the century, I asked an innocent question, prompted by an urbanist’s curiosity about a rapidly transforming neighborhood: “Do you guys own your building?” The attendant’s eyes narrowed suspiciously, “You one of those art people?”) In between the warehouses and factory lofts west of 10th Avenue were garages, auto repair shops, and service stations in sufficient quantity to amount to a veritable gasoline alley by 1920 or so. By the time Berenice Abbott photographed the area in the mid-1930s as part of Changing New York, it was possible to see in them a certain kind of beauty.

Beautiful or not, gas stations and other auto-oriented businesses don’t fit tidily into most gentrification scenarios. They are slippery, liminal places: half industrial, half commercial, full of grease, grime, and low margins. And if they’ve been around long enough they are frequently contaminated brownfields in need of remediation. At the same time, whether we like it or not, they are absolutely essential to our car-bound way of life, even in as transit-oriented, bike-friendly, and walkable a place as New York City.

All those taxis have to get their gas somewhere, just not, anymore, at 24th and 10th. Recently, the Times took note of a phenomenon it called “Manhattan’s Vanishing Gas Stations,” though it’s happening in all the boroughs, and, in fact, across the country. Manhattan lost 44% of its stations in less than a decade; the city lost 35%; the nation as a whole lost 25% in two decades. So it turns out that Sheep Station at Getty Station is more appropriate than its developers realized. Their aim was “to incorporate a classic twentieth century American icon into the contemporary art dialogue,” but in Luxury City, the gas stations are quickly becoming museum pieces.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.