Speculations on the Origins of the Jersey City; or, Geographies of Drinking, cont’d. 21 February 2015

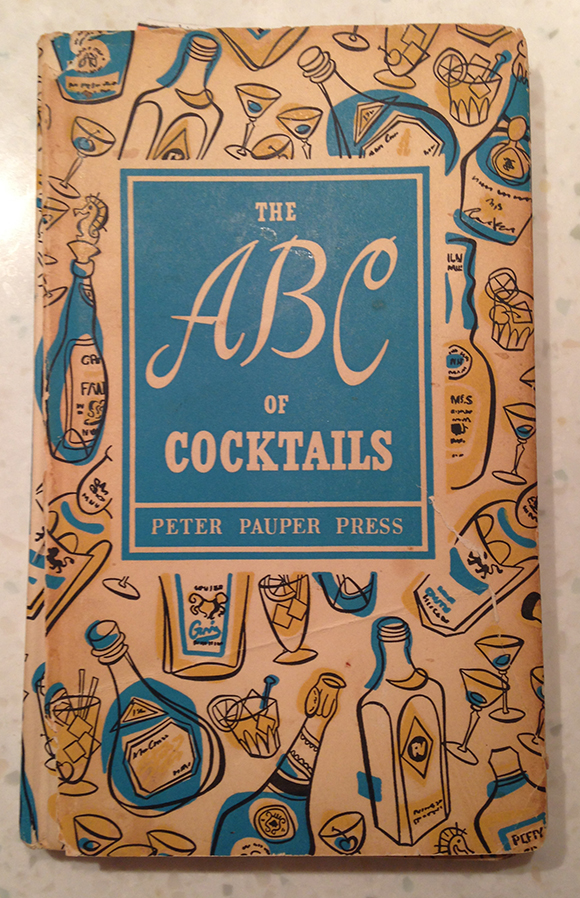

Some months back, I chanced upon an unfamiliar book on a shelf in my parent’s kitchen: a little volume on cocktails that was jazzier than the venerable Mr. Boston (the book to the left) and less learned than William Grimes’ Straight Up or On the Rocks (the book to the right). Published by Peter Pauper Press in 1953, The ABC of Cocktails was part of an extended series of whimsical, food-oriented primers edited by Edna Beilenson and illustrated by Ruth McCrea (and now reissued in kindle editions). Though filled with lightweight rhymes (“Alcohol’s a temptress, alcohol’s a flirt, She’ll either raise you to the skies, Or drop you to the dirt.”), the recipes were intended for “experienced drinkers,” rather than “amateurs [and] maiden aunts.” Being an experienced drinker myself, I gave The ABC serious consideration. The cocktails it included went well beyond the standard repertoire, even that of our expansive updated-classics era: Ward Eight, High Hat, Third Rail. But what really caught my eye, vis-a-vis a broadening interest in the nexus of geography and spirits, was an impressive number of drinks with place-based names. Not just usual suspects like Manhattan and the Bronx, but Hong Kong, Havana, Kingston, Monte Carlo, Nevada, and Florida. Of these eponymous drinks, one in particular stood out.

Some months back, I chanced upon an unfamiliar book on a shelf in my parent’s kitchen: a little volume on cocktails that was jazzier than the venerable Mr. Boston (the book to the left) and less learned than William Grimes’ Straight Up or On the Rocks (the book to the right). Published by Peter Pauper Press in 1953, The ABC of Cocktails was part of an extended series of whimsical, food-oriented primers edited by Edna Beilenson and illustrated by Ruth McCrea (and now reissued in kindle editions). Though filled with lightweight rhymes (“Alcohol’s a temptress, alcohol’s a flirt, She’ll either raise you to the skies, Or drop you to the dirt.”), the recipes were intended for “experienced drinkers,” rather than “amateurs [and] maiden aunts.” Being an experienced drinker myself, I gave The ABC serious consideration. The cocktails it included went well beyond the standard repertoire, even that of our expansive updated-classics era: Ward Eight, High Hat, Third Rail. But what really caught my eye, vis-a-vis a broadening interest in the nexus of geography and spirits, was an impressive number of drinks with place-based names. Not just usual suspects like Manhattan and the Bronx, but Hong Kong, Havana, Kingston, Monte Carlo, Nevada, and Florida. Of these eponymous drinks, one in particular stood out.

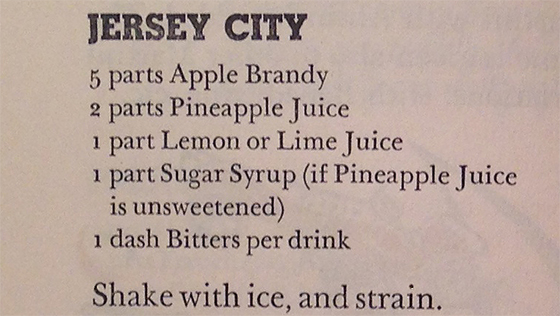

The Jersey City appears on page 34, in between the Jack Rose (immortalized in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises) and the Jersey Sour. Like both of those drinks, the key ingredient in the Jersey City is apple brandy, a.k.a. applejack. As noted in an earlier discussion of the Newark cocktail, applejack can rightly be considered the state spirit of the Garden State, having been produced in Jersey since shortly after the first European settlers arrived. Though grains don’t grow well in New Jersey, fruit trees do; apples, in particular, have been called the foundation of the state’s “fruit culture.” It goes without saying that in the 17th and 18th centuries, folks were drinking those apples as frequently as they were eating them, the fermentation of excess harvests having long been an economic, as well as social, necessity.

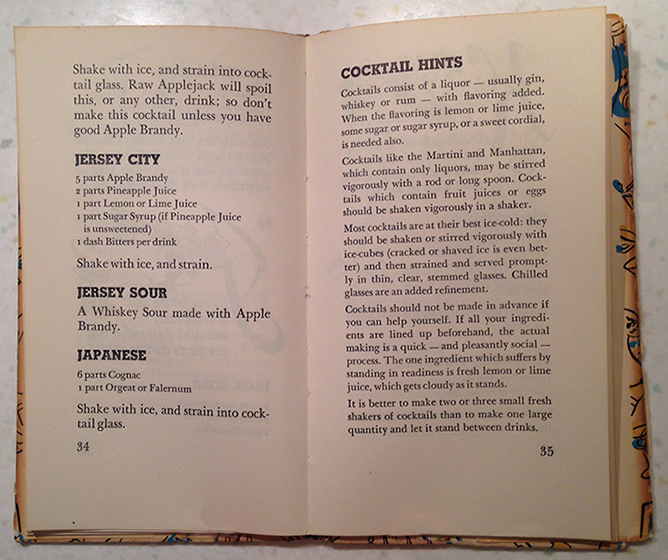

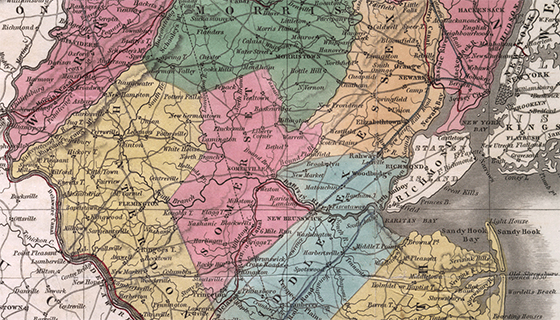

According to some sources, the need to get applejack from producer to consumer was critical to the development of the state’s infrastructure, spurring the construction of plank roads and gravel highways north and south, east and west. Early in the 19th century, supporters of the Morris Canal reversed this logic, arguing that the speed and efficiency of an engineered waterway meant that New Jersey growers could bring their apples to the markets of Philadelphia and New York without turning them into spirits. When the Morris Canal finally opened in the 1830s, the supposed result was “a large increase of profit to the farmer and of good morals to the community.”

That may be, but it’s hard to imagine not needing a few slugs of Jersey Lightning during that five day, 100+ mile journey from Phillipsburg on the Delaware to Jersey City on the Hudson, through the canal’s 23 locks and, especially, its 23 incline planes (which lifted each barge a whopping total of 1600 vertical feet). Regardless, given how quickly the railroad made the Morris Canal obsolete (completing the same journey in about five hours), its impact on the state’s morals was probably as short-lived as its profits. By the eve of prohibition there were more than 400 applejack distilleries operating in New Jersey.

Today, only one is left standing: Laird’s of Scobeyville, Colts Neck Township, Monmouth County. Members of the Laird family have been making applejack in New Jersey for twelve generations (even if their apples now come mainly from Virginia). Their outfit is the oldest licensed distillery in the United States and one of the oldest family owned and operated businesses in the country. Applejack’s bona fide New Jersey terroir is, therefore, unimpeachable. Having adequately explained the presence of “cyder spirits” in a cocktail named for New Jersey’s oldest, if not yet largest, city, we can now turn to less obvious dimensions of the Jersey City‘s cultural geography.

To put it another way: what’s up with the pineapple juice? As Imbibe recently observed (about a different drink with a similar provenance), “Jersey City isn’t exactly a tropical paradise.” But what kind of a place is it? More precisely, what kind of a place was it when The ABC of Cocktails appeared? The WPA Guide to New Jersey (1939) had this to say: “Millions of people carelessly regard Jersey City as a necessary rail and motor approach to Manhattan.”

[For drivers en route to the Holland Tunnel, necessary evil is probably a better description, whether in 1939 or today. Above is an Arthur Rothstein photograph shot for the FSA/OWI; below is an iPhone photo shot by a commuter sitting in what he called “ridiculous” traffic. The Seaboard cold storage building is evident in both.]

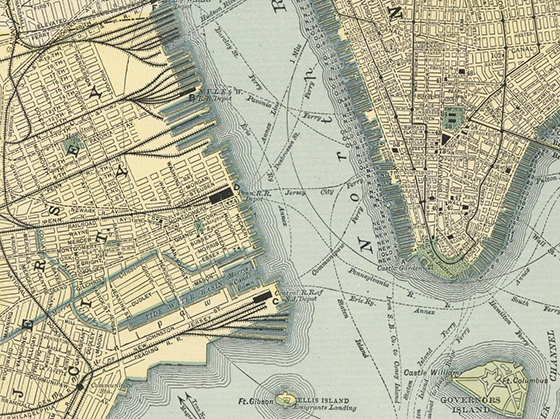

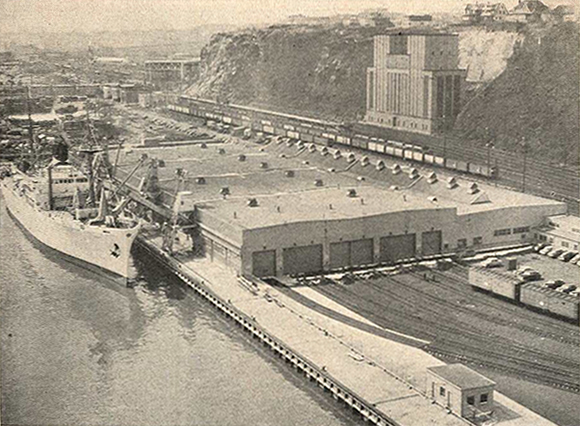

And yet, the Guide continued, “the propitious location of the city, close to the tremendous financial and consumer markets of New York City and metropolitan New Jersey, is an advantage equaled by its geographical position on upper New York Bay. This favorable situation has furnished Jersey City with shipping facilities which, in turn, have drawn motor routes and rail lines.”

This is not a minor point: Jersey City is On the Waterfront, even if Elia Kazan’s iconic film (1954) about longshoremen, unions, and corruption was shot on location one town over, in Hoboken.

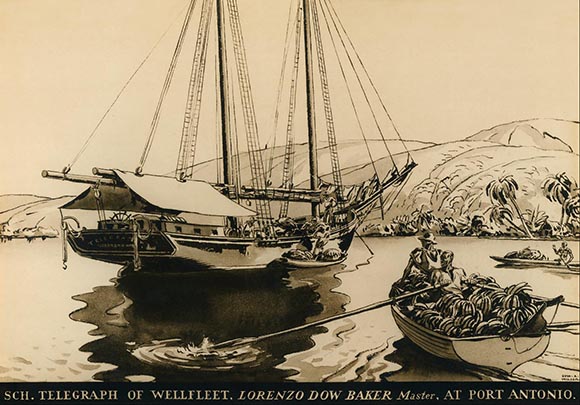

It is a little known fact that the enterprise that became the United Fruit Company began in Jersey City in 1870, when a sea captain named Lorenzo Dow Baker returned from Jamaica with 160 bunches of bananas and sold them on the streets of JC at a considerable profit. In 1899, Baker merged with his nearest competitors to become the United Fruit Company of New Jersey (state laws passed in the 1880s were famous for their generosity to big business; Standard Oil of New Jersey incorporated in 1885).

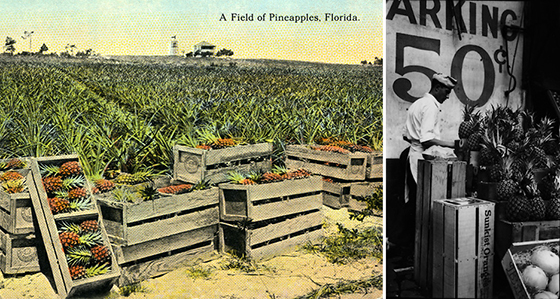

Around the same time, the United Fruit Company started growing pineapples in Florida, which was then the world’s largest pineapple exporter, and then shipping them north to the “tremendous” consumer markets of the NY/NJ metro area. Thus, however tenuously, we have established a connection between the pineapple and Jersey City, between the pineapple juice and the Jersey City.

Around the same time, the United Fruit Company started growing pineapples in Florida, which was then the world’s largest pineapple exporter, and then shipping them north to the “tremendous” consumer markets of the NY/NJ metro area. Thus, however tenuously, we have established a connection between the pineapple and Jersey City, between the pineapple juice and the Jersey City.

To conclude: by the middle of the 20th century, in between propping up Central American dictators and violating anti-trust laws, the United Fruit Company continued to dock its ships at Pier B (at the foot of Exchange Place) in Jersey City, while also operating the world’s largest mechanical banana handling facility in nearby Weehawken (at the foot of the Lincoln Tunnel ventilation towers). My research to date has not revealed where the pineapples were handled at mid-century, but today they are processed further inland on Jersey City’s West Side. The anonymous container warehouses hard by the Newark Meadows may lack the romance of the Hudson River, but the work still has its hazards: in 2013 a stevedore was nearly crushed when 1500 pounds of sliced pineapple came toppling out of the container he was unpacking.

Back on the waterfront, Jersey City has a post-industrial sheen that will be familiar to anyone who’s followed urban transformation since the 1970s. As for the Jersey City, even without the backstory, it’s a damn good cocktail.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.