Tents and Tarmac 3 June 2012

I’ve been contemplating the extremities of Flatbush Avenue because recently I spent a couple of days at Floyd Bennett Field, just off the road’s southern terminus, the last exit before the bridge to the Rockaways. Actually, I spent a couple of nights at Floyd Bennett Field, too.

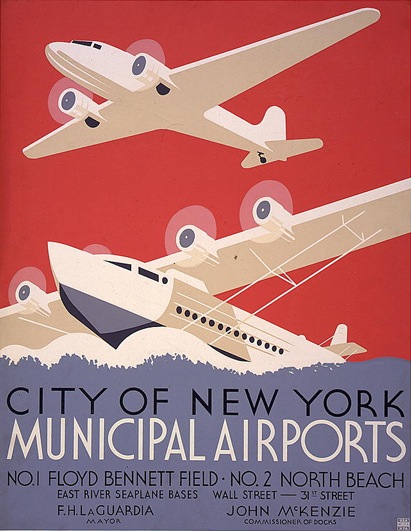

Not because I have a particular passion for aviation, though I’ll admit to watching planes take off from Newark while eating Swedish meatballs at the IKEA in Elizabeth. Not because New York City’s Municipal Airport No. 1 has considerable urban and architectural appeal–concrete runways, art deco hangars, WPA murals. Not even because visiting what is now part of the Gateway National Recreation Area meant I’d be able to add a few more of those Vignelli-designed National Park Service brochures to my collection.

Compelling reasons, to be sure, but not prime motivations. I spent two days and two nights at Floyd Bennett Field because I was camping.

Now, I’m no stranger to roughing it in the city: slept on a sidewalk near the Delacorte to get tickets to the Mike Nichols/Tom Stoppard production of Chekov’s The Seagull with Meryl Streep; relieved myself behind a bush on a traffic island in the shadow of the Williamsburg Savings Bank while running the marathon. Compared to being out there at Floyd Bennett Field, though, all that was just quotidian urban adventuring.

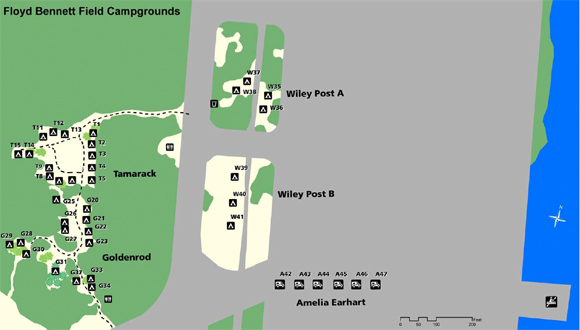

This was proper camping–tents, sleeping bags, pit toilets, flashlights, solar showers, non-potable water.

Open fires, s’mores, even campfire songs–if a Donna Summer im memoriam playlist on an iPhone counts.

This was camping like it’s done in the Adirondacks or the Badlands or Yellowstone. Except we were in New York City, in Brooklyn, off Flatbush, at an airfield, by a runway.

There were no coyotes or bears, but some wily raccoons helped themselves to our baked goods. There were no mountains or canyons, but the 747s out of JFK were close enough to make out the airline logos. There were no ancient petraglyphs or abandoned homesteads on the hiking trails, but we did find evidence of earlier inhabitation: a lonely fire hydrant slowly consumed by the returning grasslands.

And that’s how it should be, because you don’t go to Floyd Bennett Field for the nature itself–you go to witness how humans have transformed the nature, turning the wetlands of Dead Horse Bay and Barren Island into a Dutch agricultural village, then a noxious industrial settlement of rendering plants and fish oil factories, then an airport built on millions of cubic yards of landfill.

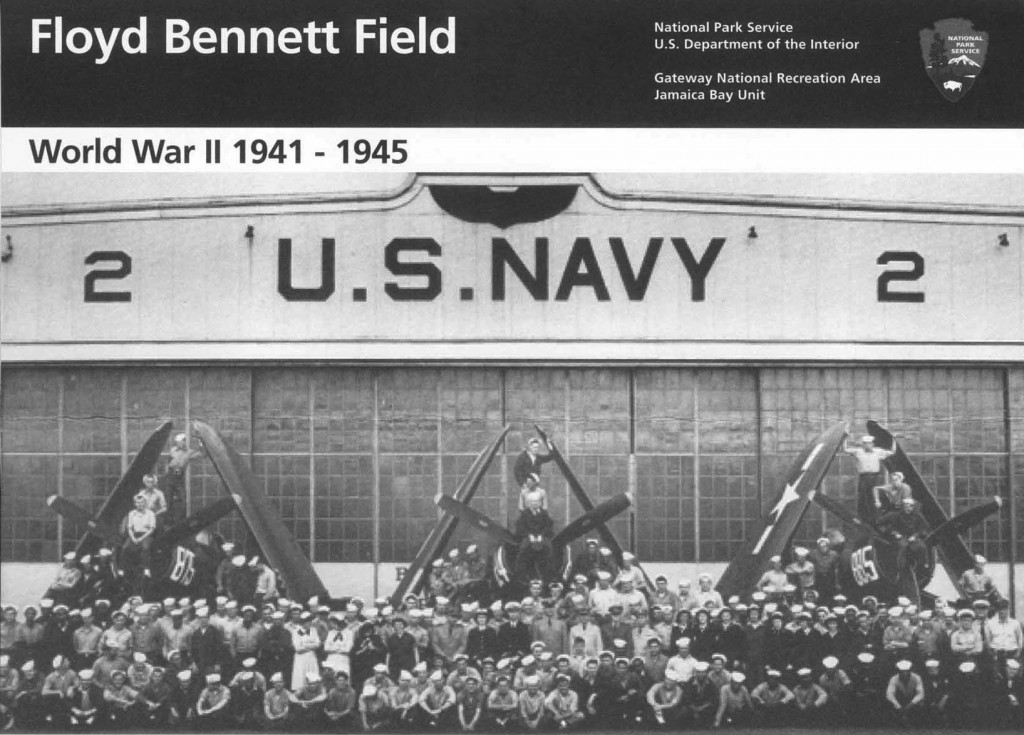

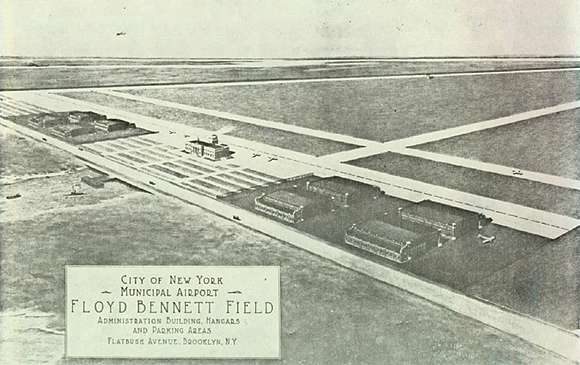

Though the airport opened to great fanfare in 1931, and played an important role in aviation history, by the 60s it was obsolete. It was too far away from the city’s population centers for commercial viability and had trouble competing with Newark Airport from the beginning. World War II gave it new life as a Naval Air Station but once North Beach/LaGuardia and Idewild/JFK came online, Floyd Bennett Field’s days were numbered. The Coast Guard operated an air station here until the late 80s and the NYPD still has an active helicopter base on site, but the only fixed-wing craft flying at FBF now are remote-controlled miniatures. That’s sort of OK because it leaves the runways free for other uses.

Walking along those runways, which range from 3,000 to 7,000 feet in length, is the closest I’ve ever come to finding big sky country in NYC.

This effect is intensified if you lay down on the tarmac.

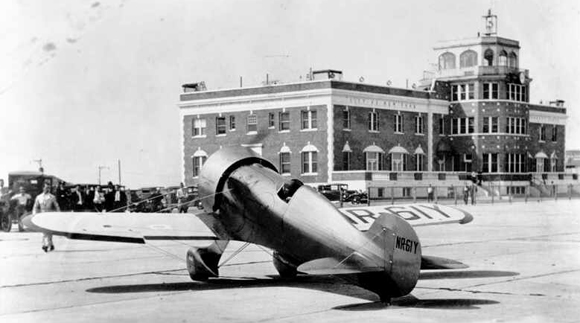

And then there are the buildings. The terminal, freshly restored as the Ryan Visitor Center, is lovely, though its interpretive displays are hardly state-of-the art (the newsreels, however, are groovy). Outside, it’s a chipper Georgian revival pile of red brick and concrete (well, cast stone, concrete’s putting-on-airs cousin) that dates to 1930 and tops out with a winged globe on the parapet above the entrance.

Out back, the neo-colonial air traffic control tower, designed by one Hugh McLaughlin of the Department of Docks, happily conflates historicism and high tech.

This was even more obvious before the Navy renovated it in the 40s. Are those really keystones above the arched plate glass windows?

The control tower is so weird and American it’s like a missing chapter from Delirious New York. The skyscraper wasn’t the only way to conquer what Koolhaas called “the frontier of the sky.”

In 2012, though, the hangars are the real attraction.

Four of the hangars closest to Flatbush (to the left in this period rendering) house a recreation concession called Aviator Sports, a place with such a before-Brooklyn-was-hip-old-school-outer-borough vibe that it’s got an airport version of the Fremont Street Experience inside: “the historic aviation-themed entryway, welcome center, and thoroughfare.” I’m not sure why you need an aviation theme at an actual aviation site, but there’s much I don’t understand about marketing.

We didn’t venture in, preferring the authenticity of Hangar B, which is closer to the campgrounds anyway, straight down Runway 24 on the edge of Jamaica Bay. Built by the Navy in 1941, it’s a workaday steel shed that is now home to the Historic Aircraft Restoration Project.

On the morning we visited, Hangar B was full of old planes being lovingly restored by old plane enthusiasts, meaning the volunteers were nearly as historic as the aircraft. The military planes are mostly from WW II and, for a genuine aviation-theme experience, you can climb inside a Lockheed P-2 Neptune retired from the Navy. If you’re not claustrophobic you can crawl forward to the nose of the plane and sit in the gunner turret while your friends take pictures of you.

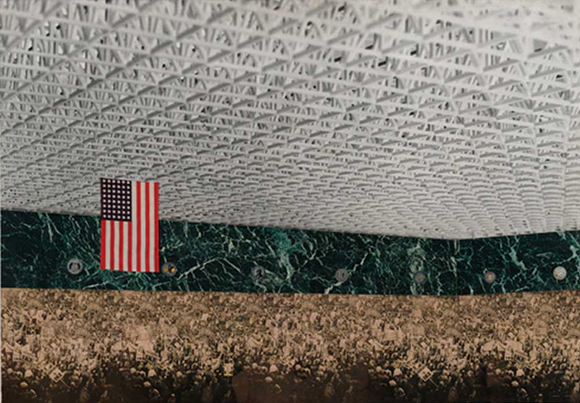

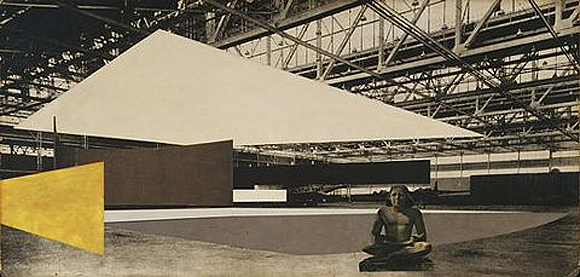

Aside from the planes, the hangar itself is pretty impressive, covering more than two acres and boasting some serious clear spans. With an outsize American flag hanging from the open trusswork, Hangar B reminded me of a famous Mies collage from the 50s, the one with an outsize American flag hanging from the open trusswork.

The pure modernism of his 1953 Convention Hall riffed on the borrowed modernism of his 1942 Concert Hall–that one was set in an actual industrial building, designed by Albert Kahn in 1937.

A satisfying historical footnote: the Kahn building Mies’ borrowed for the Concert Hall was an airplane factory nearly contemporary with FBF Hangar B.

In the Mies in America catalogue, Phyllis Lambert notes that, when he was making this collage, Mies used Kahn’s building as a “ready-made structure.” If redeploying an industrial building for a cultural program was mildly shocking at mid-century, it was less so by the century’s end, at least for the sort of people who travel to places like Marfa, North Adams, and Beacon. Visiting the Chinati Foundation or Mass MoCA or Dia and wandering through those enormous ready-made structures filled with enormous modern and contemporary art is sort of like finding yourself inside that Mies Concert Hall collage.

The enormous ready-made structures at Floyd Bennett Field have that same poetic potential. If you can repurpose an artillery shed, a capacitor plant, and a box factory for Judds, LeWitts, and Heizers (and Flavins, Serras, Bourgeoises, etc.), why not an airplane hangar? Why not four airplane hangars?

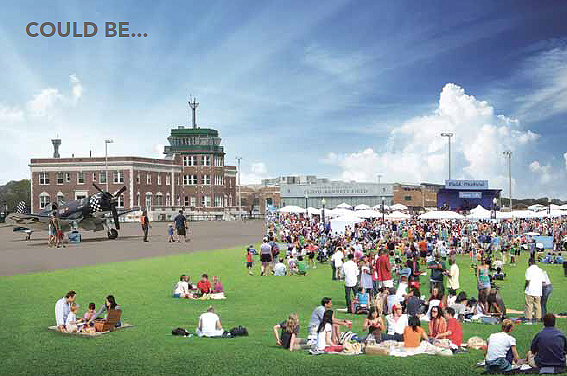

The ruin porn crowd might prefer to keep them as is, but that’s not going to happen. Last year, a Blue Ribbon Panel–whose members included Christopher Ward of the Port Authority, Robert Yaro of the Regional Plan Association, and landscape architect Diana Balmori–issued a report that described Floyd Bennett Field as “the next jewel in New York’s urban park crown” and called for turning FBF into “an iconic urban national park.” Broken glass and abandonment aren’t really part of the National Park Service aesthetic (to say nothing of Bloomberg’s New York), and the buildings of “Hangar Row” are now destined for “active uses”–whatever that means.

The picnicking New Yorkers in this rendering from the report sure look happy, but pitching a tent by the tarmac isn’t going to be as much fun with all of them around. So book a campsite while the place is still mostly quiet. The urbanism is rough and the nature is ragged, but right now Floyd Bennett Field has a special kind of beauty. And at $20 a night for up to six people, it’s also got the cheapest lodgings to be found in any of the five boroughs.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.