Chips and Chairs 13 September 2013

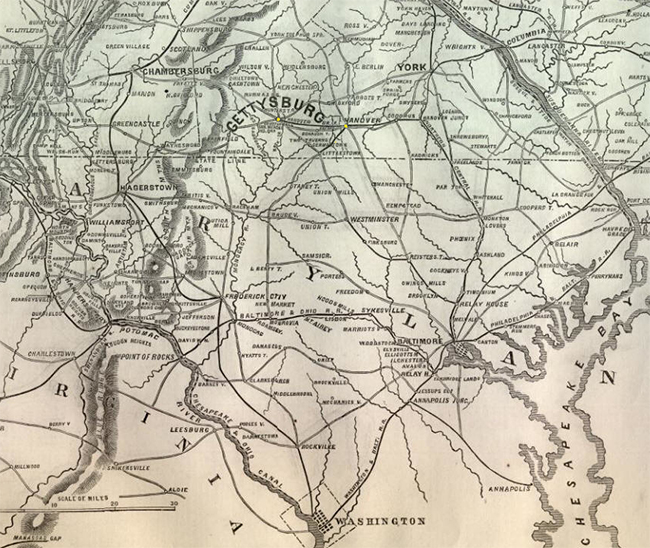

Hanover, Pennsylvania sits six miles north of the Mason-Dixon line at nearly the same longitude as the District of Columbia. During the Civil War, this location, along with a critical east-west rail line, made it inevitable that the town would get caught up in the northern invasion Robert E. Lee launched in the summer of 1863.

Hanover was raided by Confederate troops in late June, and the skirmish there on the 30th–between the cavalries of J.E.B. Stuart and the 18th Pennsylvania under Judson Kilpatrick–is frequently described as the prelude to the better-known and far bloodier engagement that began the next day, 14 miles west, at Gettysburg. This summer marked the sesquicentennial of the Civil War’s deadliest battle, so it was no surprise that the reenactors turned up in force in Hanover, too–along with 1,000 spectators, at least according to The Battle of Hanover Reenactment page on Facebook.

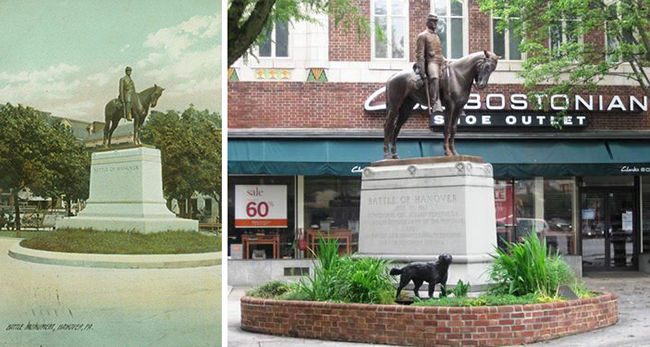

I got to Hanover too late for the faux fighting and had to content myself with contemplating The Picket, a statue originally installed in Hanover’s Center Square on the 50th anniversary of the battle. Standard war memorial stuff, the sculpture by Cyrus E. Dallin depicts an alert Union soldier on sentry duty astride a sleepy looking horse (in the attitude of horse and rider, it’s the exact opposite of the Sioux Chief and his mount in Dallin’s iconic Appeal to the Great Spirt, outside the MFA in Boston). Once dominating the intersection of Hanover’s major streets, The Picket was relegated to a widened sidewalk to improve traffic circulation at some point in the middle of the 20th century. If it’s lost some of its dignity with the addition of that dog statue, from a nearby cemetery, The Picket makes a nice counterpoint to the art deco detailing of the commercial block behind it. Not unlike The Picket, the tenant of that block–Clark’s Bostonian Shoe Outlet–is a reminder of something out of Hanover’s past, something once essential to its identity, but now merely vestigial.

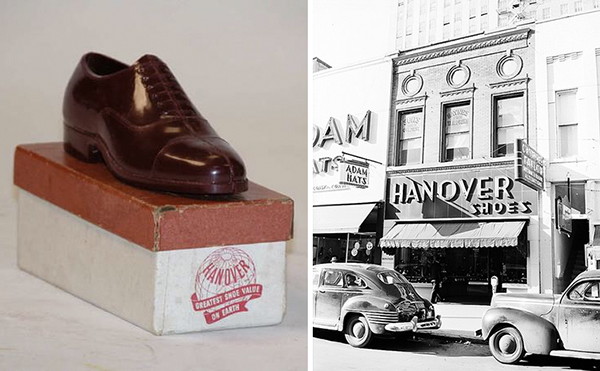

At the turn of the last century, Hanover was a manufacturing center dominated by a local shoe company whose factory was just a few blocks north of Center Square and whose retail outlets marketed the town’s name across the United States. In a pattern all too typical of industrial communities (large and small), Hanover Shoes was a source of economic vitality until the late 1970s when the company began a staged evacuation of the town, moving its factory first to a nearby suburb, then to West Virginia, and eventually overseas, the later shifts following Hanover’s takeover by UK-based Clarks.

In another typical pattern, after Hanover Shoes abandoned its original factory, the complex moldered on the verge of collapse for several decades until the original block was renovated by private developers into not-quite-loft residences in 2003. For those interested in a Hanover pied-à-terre, 1330-square foot 3-bedrooms are currently renting for just over $700. But I hadn’t come to Hanover to look at industry past; I’d come to look at industry present.

Given my roadfood predilections, some readers might assume that Hanover’s status as a regional snack food capital is what drew me here; in truth, that was an added bonus, as was the fact that my visit involved lunch at Original Famous Hot Weiner, in business for 90 years and operating at this location since 1928. Spelled in the Jersey fashion, with the E before the I, the Hanover version of the Texas Weiner is also of Greek ethnicity and includes not-too-smoky chili, a slightly piquant sauce, and plenty of chopped onions. Though Nicholas Mavros’ original lunch stand suffered a bad interior renovation in the early oughts, the exterior is still thankfully intact, as long as your idea of “intact” includes, as mine does, circa 1940s perma-stone, aluminum awnings, and hand-painted signs all covering the lower-level of a handsome mansard-topped Italianate nearly contemporary to the Civil War. I was tempted to dismiss the hip-roofed entrance pavilion for adding a sour note to the otherwise happy effect of the hodge-podge modernization, but now I’m wondering if it’s not a favored local motif because one turns up very nearby at Synder’s of Hanover.

Snyder’s sort of counts as both old industry and new industry: folks have probably been making pretzels in Hanover since the Germans arrived in the 18th century, but the company dates only to the early part of the 20th. Its factory, most decidedly, does not. It’s a long, low shed of a building whose only distinguishing feature (aside from that hipped canopy) is a facade veneered in dun-colored corrugated pebble-crete. It makes a nice backdrop for the trees that line the parking area, but I’d be surprised if that was a factor in this particular design decision.

Much more interesting is the solar farm just across PA-116, the state’s largest on-ground type, covering 26 acres. Snyder’s completed the farm in 2011 and the company estimates that it’s reducing the factory’s energy costs by 30% and will cut CO2 emissions by 230 million pounds over 25 years. I wish I could report that Snyder’s factory tour is as forward-thinking as its energy plan. Alas, it’s little more than an excuse to get people to spend money on the copious snack foods for sale in the factory store–including lots of stuff not made in this particular factory. Growing up in Philadelphia, Snyder’s were our preferred brand of hard pretzels, and I still think they’re pretty good, so I was disappointed by the 30 minutes of please-keep-moving-no-cameras-allowed that counted as Snyder’s factory experience. Which is not to say we didn’t buy our share of pretzel varieties, and while we indulged in a few novelty shapes, we drew the line at novelty flavors.

It may be that I’ve been ruined for all factory tours because I got to tour Hershey (50 miles northeast of Hanover) when you could still walk inside the actual factory. All those bubbling vats of chocolate–to say nothing of the aroma–made quite an impression on me as a small child. When I visited Hershey again, on a grade school trip, the factory was closed to visitors and the tour, such as it was, consisted of a lame, Disney-inspired ride that simulated chocolate manufacturing from harvesting the beans to wrapping the candy bars–think It’s a Small World with cacao plants. Then again, maybe that original visit to Hershey is the reason I’m such a sucker for a factory tour, driving the extra miles, waiting for the next guide, doing whatever it takes to get the chance to watch stuff being made. Whether it’s cheese curds in Tilamook or pickup trucks in Dearborn, the tour I’m on is always the one that maybe, just maybe, will give me the same giddy, visceral thrill as the chocolate factory back in the day.

This didn’t quite happen at the other snack food factory we visited that day, though time spent at Utz was infinitely more satisfying than at Snyder’s–and the difference may be between a family-run enterprise and a huge corporation. Snyder’s merged with Lance in 2010 to form a company second only to Frito-Lay in terms of salty snacks produced in North America. Until two years ago, Utz was exclusively a regional brand, with all of its manufacturing based in Hanover; today it’s still run by descendants (3rd generation) of William and Sallie Utz, who started selling their chips at local farmers markets in the early 1920s.

Something of that mom-and-pop vibe still hangs in the air at the Utz factory, sort of like the frying oil, or maybe it’s just the unguarded informality of the place: we parked adjacent to an 18-wheeler dumping its potato payload right onto the beginning of the assembly line.

Utz used to chip Pennsylvania potatoes exclusively, but the company’s expansion now requires it to source them from up and down the east coast, following the seasons; these taters were from Virginia. Though the Utz factory tour, like Snyder’s, consists of a glass-enclosed gallery elevated above the factory floor, it’s completely self-guided and the viewing stations are much closer to the action.

This means we got to walk slowly through the gallery, watching those potatoes become chips before our eyes. Workers on the line helped them along, from the truck through washing and sorting, slicing and frying, salting and seasoning, and bagging and boxing.

At the critical moment when the sliced potatoes emerge from the fryer, the line is almost at the same level as the gallery. That’s up close and personal with enough starch and fat to make you swear off snack food, unless it has the opposite effect, which is probably more likely, especially since an Utz ambassador, a retired worker when we were there, gives you a little bag of chips on your way out.

We didn’t really need these samples because we’d already stocked up at the Utz outlet store, located in what was the company’s first large-scale factory, built in 1949 just north of downtown Hanover and a few blocks away from the current center of production.

It’s a bit run down but you hardly notice that with so much glazed brick and glass block to admire. The signage of the office block is equally praiseworthy: aluminum channel letters with red interiors and neon tubes, the slenderness of the U-T-Z making the Os in P-O-T-A-T-O seem like almost platonic forms. Above the old production building are the superstructure and oversized letters of what must surely rank as a prominent landmark of the Hanover skyline. But I was equally distracted by features at ground level.

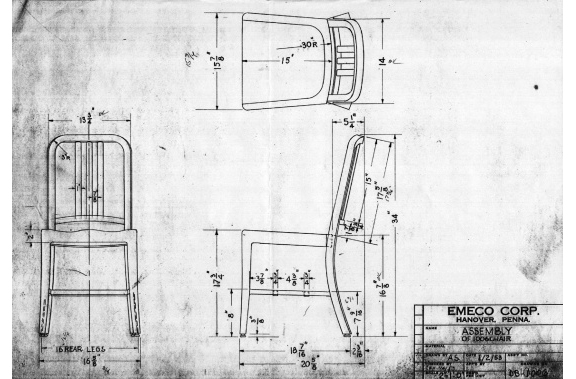

Peering through the windows of the office block, I noticed a beat up aluminum chair of roughly the same vintage as the building. With a slightly curved upper frame and three vertical bars serving as the back, it was instantly recognizable. That chair was a Navy Chair, an Emeco 1006 chair, the very chair that brought us to Hanover in the first place.

The 1006 is an American icon that’s been manufactured in Hanover by the Electrical Machine and Equipment Company since 1944, when Emeco got the government contract that would keep it in business for the next half century. The Navy needed a chair that was strong and lightweight, and impervious to salt, water and other conditions at sea (including non-magnetivity so it wouldn’t interfere with sensitive equipment). The 1006 fit the bill so perfectly that it nearly bankrupted the company: though government and institutional orders sustained Emeco for several decades, the chairs were so close to indestructible (officially, they are meant to last 150 years) that replacement orders were rare.

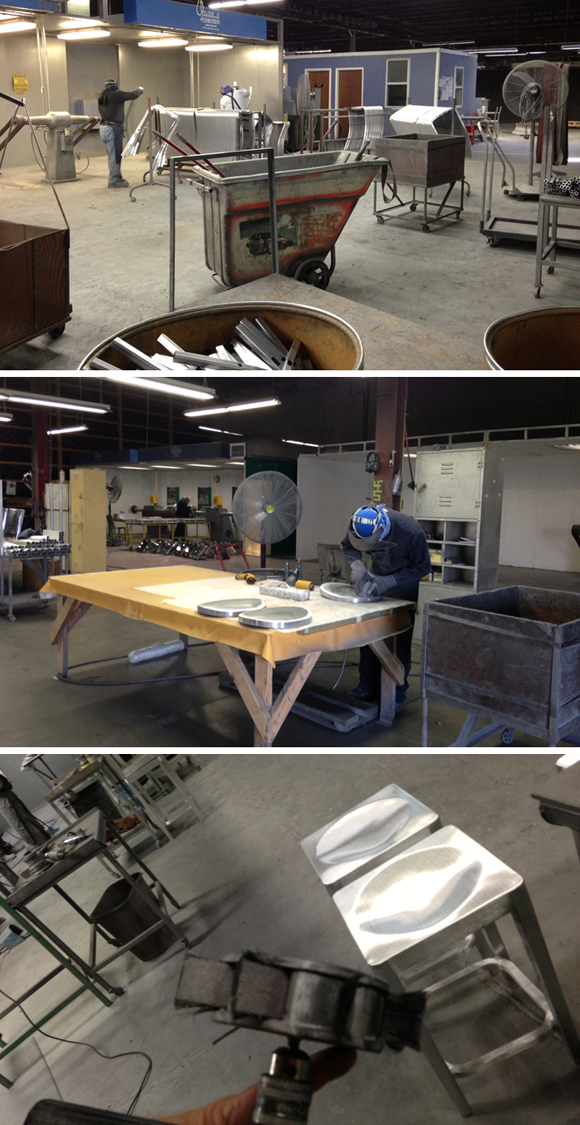

This endurance was the inevitable result of Emeco’s 77-step manufacturing process, which emphasized an extremely high level of quality craftsmanship. It still does, as I saw firsthand when touring the factory. At Emeco, this didn’t mean watching from afar as chairs whisked by on an assembly line; it meant walking the factory floor with only a pair of goggles separating me from the blow torches, the metal cutters, the sanding machines, and the acid baths.

As we moved from station to station, our tour guide (Pete Harmon, who’s been with Emeco for nearly five decades) explained each step in the process. Along the way, we saw workers forming the the Navy Chair, grinding the Kong Chair; polishing the the Emeco Stool, and finishing all of them with American-made glides. Slowly and methodically, the 54 workers at the Hanover plant produce around 1,000 Navy Chairs per month.

In an age of hyper mass production, that’s not a lot of output and, indeed, it’s a sharp decline from the quantities Emeco produced in the 50s and 60s. Since then Emeco has been forced to reinvent itself, principally by continuing to make chairs with the same painstaking attention to detail as it has since the 40s. Because of this, Emeco didn’t so much reinvent itself as reposition itself. In the late 90s, Emeco’s current president, Gregg Buchbinder (whose family bought the company in 1979), realized that even while large institutional orders were shrinking, small orders from designers and design-related companies were on the rise. The Navy Chair, it turned out, had a cult following, and Buchbinder realized that cultivating relationships with the Navy Chair’s fans was key to Emeco’s financial sustainability. It didn’t hurt that the aluminum Emeco used to make the Navy Chair, of which 80% is recycled, gave the company a sheen of environmental sustainability as lustrous as the 1006’s brushed finish.

The turning point for Emeco came in 1997 when Philippe Starck was working with Ian Schrager on the redevelopment of the Hudson Hotel in midtown Manhattan. By then, the boutique hotel craze they ignited with the Royalton and the Paramount was nearly a decade old, but you couldn’t tell that by looking at the Navy Chairs Starck had installed in the Paramount on West 46th Street (designed by Thomas Lamb, the original Paramount opened in 1928).

In graduate school a few blocks away, my friends and I retreated to the Paramount only on those rare occasions when we were feeling flush, mounting the Lapidus-inspired staircase to the mezzanine bar where the Navy Chairs, fitted out with canvas covers, epitomized the retro glamour of that particular moment of Clinton-era urban revitalization. For the Hudson, Starck again turned to the Navy Chair, using it as a point of departure for an entirely new design–one that, Starck later recalled, “washed the details” from the original 1006 to create what would become the first new chair added to the Emeco line in more than three decades. In fact, Starck didn’t wash away every detail: like the Navy Chair before it, the Hudson seat is still modeled (according to legend) on Betty Grable’s ample backside.

It takes eight hours of hand polishing to achieve the mirror finish of the Hudson Chair, and even on the factory floor they are so beautiful they make you swoon, or at least want to lean in close and check your hair and lipstick. That’s certainly the effect they had when I saw them at the Emeco booth at this year’s International Contemporary Furniture Fair at the Javits Center, gleaming against the pure white of the museum-like display.

There’s nothing quite so elegant back at the factory. Emeco is not Vitra: the storeroom-cum-showroom is more haphazard than curated, more grandma’s attic than MOMA design collection. And that’s ok.

Emeco doesn’t put its chairs on pedestals in Hanover because in Hanover all those chairs, whether designed by Philippe Starck or Frank Gehry or Norman Foster or Jean Nouvel or Andrée Putman, are less objects of desire, than objects for sitting. In Hanover the chairs are unburdened by the cultural baggage they carry out in the world, which is a good thing given what they’re made to bear inside the factory.

Out in the world myself, I walked across the lawn to get a good look at the factory. The aluminum Emeco sign–made on site, of course–looked brilliant in the sun. I could pretend that I stood there thinking about the effects of offshoring manufacturing and the persistence of craft in post-industrial America.

But really, I was thinking about the cool stuff they make at Emeco, and how cool it was that I got to see that stuff during what I can now happily describe as my best factory tour ever.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.