Remembering Ma Bell (& Aunt Lois, too) 28 June 2013

Thirty years ago this summer, consumers across the United States were starting to contemplate what the impending break up of AT&T (effective on January 1 of 1984) was going to mean for telephone service and billing. Having just graduated from high school I was, as yet, unconcerned with choosing a service provider or paying for long distance calls, but I was still paying attention to the consequences of divestiture, at least in terms that were tangible to me then–namely that my mother had decided to purchase all of the telephones currently installed in our house. Until that point, like everyone else, we had leased our equipment from Ma Bell. Now, suddenly, those same phones possessed the aura of ownership.

But for a single Princess in the library, the phones in our house were Western Electric Model 500s, hard-wired, tabletop rotaries designed by Henry Dreyfuss beginning in the early 1950s. As indicated by their clear plastic dials (to say nothing of the CHestnut Hill exchange named at the center), our 500s were from the 1970s, but they retained the elegant sturdiness of the earliest models. As a result, they were–and still are–eminently satisfying to use. (There’s a reason Native Union‘s “original retro handset” is based on the Dreyfuss design, but their POP phone lacks the 500’s land-line, steel-guts heft.)

In the summer of 1983 my knowledge of Henry Dreyfuss was non-existent, but by the time I finished college I had acquired a passing acquaintance with his work, thanks in part to the 1986 Machine Age show at the Brooklyn Museum. By then, I had also learned a few things about AT&T because my future father-in-law worked for one of the company’s R&D divisions in Columbus, Ohio.

The photo depicts Family Day at the Columbus Labs in 1979, though it’s not clear what suburban campus was being commemorated in the backdrop. The quotidian Columbus Works, on the east side of town, opened in 1957 and the magisterial Saarinen-designed complex in Holmdel, New Jersey opened in 1962.

Either way, by the late 70s, AT&T’s outward migration from city to suburb was historical fact. That Philip Johnson’s AT&T Building was then under construction in the heart of midtown Manhattan, and would be completed in the divestiture year of 1984, is one of those ironies it would be delicious to savor if the building’s postmodernism didn’t leave such a bad taste in your mouth–and if the Holmdel campus wasn’t facing a preservation crisis as developers pursue plans to transform the 472-acre site into a live-work-shop lifestyle center, complete with townhomes, upscale spa, public promenade and a golf course.

Another irony: the original planning for this suburban Bell Labs complex also precipitated a live-work redevelopment scheme–though, as I would find out after moving to New York in the late 80s, most people viewed that one as a preservation opportunity rather than a crisis.

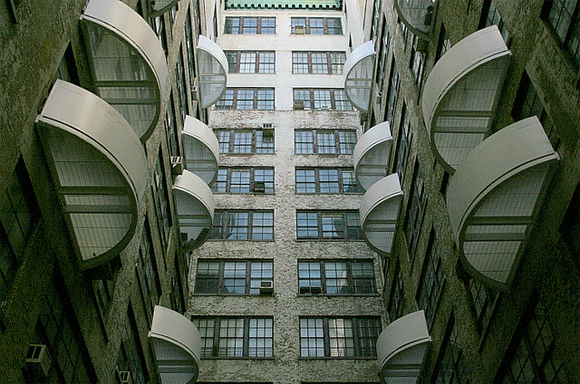

When I came to the city after college, one of the first people I met was a sculptor and jewelry maker who lived in the Westbeth Artists Community. His loft was on a high floor with a big terrace that looked south to the Twin Towers and east into Merce Cunningham’s dance studio.

For someone new to New York, it was a magical sort of place, and I’d have been convinced of that even it I hadn’t encountered Laurie Anderson and Lou Reed in the freight elevator. But Westbeth was also an historic sort of place. When the West Village complex opened in 1970, with funding from the NEA and the J.M. Kaplan Foundation (and help from a couple of zoning variances), it was the largest industrial-to-residential adaptive reuse project in the country and, according to New York 1960, the largest artist community in the world. It was also (re)designed, in the paint-it-white aesthetic we’ve come to associate with loft conversions, by a young Richard Meier–then emerging into his New York Five notoriety.

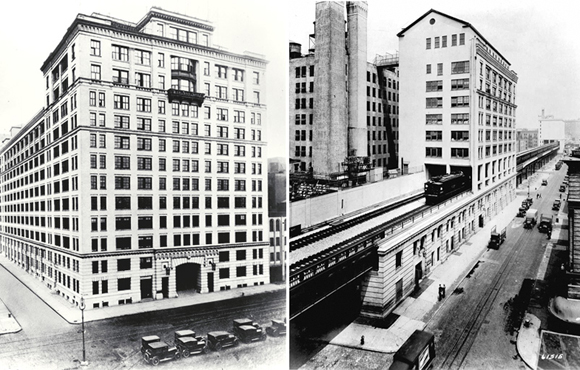

Of course, the history of Westbeth didn’t begin when the artists moved in: much of the building dates to the 1890s when Cyrus Eidlitz designed it as an office and factory for Western Electric. By the 1930s, when Vorhees, Gemelin and Walker extended the building along Washington Street to accommodate the elevated rail line that would become the High Line, it was already home to the engineers and scientists of Bell Telephone Laboratories, the legendary research division of the American Telegraph and Telephone Company. Between 1925 and 1966, an astonishing number of technological innovations emerged out of the labs on West Street, including breakthroughs in sound recording and LP records, television broadcasting, and the first binary digital computer. They designed telephone stuff here, too, pretty much inventing the idea of modern telecommunications in a great buff brick pile along the Hudson.

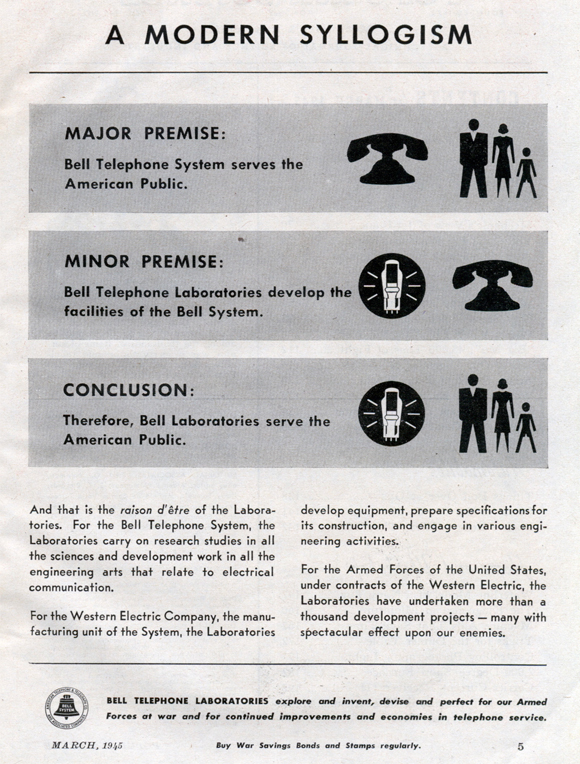

AT&T was only too happy to promote the social import of this supposedly public (i.e. not commercial) enterprise, as the company explained in an advertisement that appeared in Popular Science in March 1945.

In the final months of World War II, it may well be that the ad’s military-industrial intonations didn’t seem quite so creepy as they do now; and, given the scatter-for-safety ethos of the day, it is not surprising to find that plans were already underway to decentralize AT&T’s R&D operations. These culminated in 1966, when the last of AT&T’s researchers abandoned the West Side Highway for the, literally, greener pastures of Monmouth County where they would spend the next thirty years working on satellites, microprocessors, lasers, fiber optics, and all sorts of other things we take for granted in the 21st century.

With its expanding suburban presence, AT&T must have seemed the very model of a modern corporation at mid-century, but from a branding standpoint it was as creaky as an anti-trust Standard Oil, an uncomfortable comparison at a moment when Ma Bell’s sanctioned monopoly was coming under the increased scrutiny that would lead to its break up. And so, following the lead of other blue chip companies around the same time, AT&T decided it needed a make-over, hiring the legendary Saul Bass to update its image for a the telecom era.

Plenty has been written about the Bell logo, before and after Bass, but the designer himself described it best in the film he made to pitch the new image: “Our present look: dull. Our new look: alert. Our present look: government issue. Our new look: enterprising.” AT&T made the 27 minute film available last year, and it’s well worth watching: with its psychedelic-lite score, quick cuts, and kaleidoscopic images it’s an apt (and early) demonstration of what Thomas Frank has called “the conquest of cool” and the “rise of hip consumerism.”

The Bass identity campaign also included a proposal for uniforms and other “wearing apparel,” as he called it. These, according to the film, were functional outfits designed to make AT&T’s “rugged individualist” linesmen and installers “more efficient, look better, his job easier.” Alas, we will never know if wearing those Bass-designed stripes would have improved worker performance or created a slimming profile because AT&T declined to put the uniforms into production.

This doesn’t mean, however, that Bass’s work for AT&T left no fashion legacy, as is demonstrated in the logo-emblazoned belt buckle I recently acquired. At least I think it’s fashionable; I’m not sure its original owner would agree. The buckle belonged to my wife’s aunt, Lois Boyer Toth (1936-2013), who favored snappy pants suits, pumps, and Longchamps handbags. I can’t ever recall Lois wearing a belt, much less one with such a prominent centerpiece. I’m guessing that for Lois this was less a buckle than a token, because Lois spent the second half of her professional life with AT&T. As the story goes she was working as a nurse at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital when the president of Bell of Pennsylvania became her patient. He was so impressed with the care she gave him that he asked her to join the company.

I don’t know when Lois got this belt buckle—AT&T stopped using the bell logo at the time of the breakup, replacing it with the infamous “death star” Bass designed in 1982. What’s more important is that she kept it, through more than two decades of work, through many years of retirement. She kept the buckle long enough for her nieces to find it among her personal effects and give it to me. Who knows why she kept it—did it signify pride of employment or was it forgotten in a back drawer? Maybe it doesn’t matter. Corporations, as we all know, are not people, but sometimes a corporation, or just a logo, can conjure a person. And now, every time I wear the buckle, I won’t just think about AT&T or even Saul Bass. Every time I wear the buckle, I’ll think about Aunt Lois.

I’ve got a John Deere belt buckle, too, but that history will await another telling.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.