Inhabiting the Poor Farm 1 October 2012

They say the place is haunted. And when you encounter the Vinalhaven Poor Farm for the first time, it’s easy to understand why. It’s a rambling sort of building, with long halls and odd staircases, with forgotten rooms and creaking doors that won’t stay closed. The oldest part of the house is a traditional Cape with an attached ell, both built by James Smith (or was it John Smith) in the 1830s.

More precisely, the house is a “full Cape,” with an entrance facade consisting of two windows flanking both sides of a centrally-placed door. This opens onto a small vestibule dominated by tight curving stairs that lead up to modest bedrooms under the eaves–just the sort that could be occupied by spirits. Typical of this part of New England, the one-story ell linked the house to the barn to create what’s called a connected farm, a useful arrangement for tending to the animals when the weather was less than agreeable.

According to the local records, at least four generations of the Smith family farmed this eastern shore of Vinalhaven island, from the middle of the eighteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth, long enough for them to lend their name to the cove you still see from the house today.

Smiths remained on the land even after the Town of Vinalhaven purchase 100 acres and the connected farm buildings for $900 to use as a poor farm: Eban G. Smith and his unnamed wife served as the farm’s keepers when the first inmates arrived in July of 1894. They ran the place as a subsistence homestead, with a large vegetable garden, a couple of cows, some pigs, and chickens who seemed to have had the run of the place.

Smith, and the keepers who followed (Misters Spears, Morton, Hall, and Bunker), kept a strict accounting of the room and board he and his wife provided, noting in a ledger book (in the collection of the Vinalhaven Historical Society) all living expenses charged against the residents: cough medicine, flannel, yarn, work boots, pipes, matches, tobacco, etc. The folks who used these supplies were mostly local: widows, orphans, and indigent farmers and fishermen native to the island, or from nearby on the mainland, but the records indicate that Italians and Swedes were also at the Poor Farm in its early years.

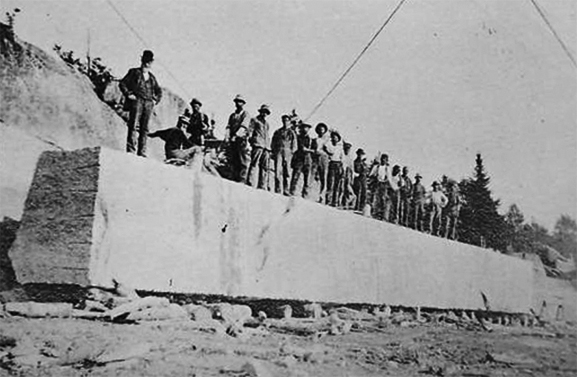

Having come to the island to work as stonecutters in Vinalhaven’s thriving granite quarries, they also had to endure seasonal layoffs and the increased mechanization of the industry, which probably explains why some of them ended up at the Poor Farm.

Before 1900, the town appropriated an additional $600 for “enlarging the house and making room to accommodate more inmates.” The original connected barn was replaced with a tall dormitory close to the road. With two-full stories plus an attic rising under a single broad gable, the dormitory was a large clapboard shed divided into small rooms on either side of a center hall.

This new wing gave the Poor Farm a more institutional appearance, but the added space proved a worthwhile investment after the stock market crash of 1929. The ledger books from the 1930s show that there were more Vinalhaven residents living at the Poor Farm during the Great Depression than at any other time in its existence. Some Poor Farmers moved in and out during this period, leaving if they found work (in island quarries or mainland canning factories), and returning when they were unemployed. Slowly, though, throughout the decade, the social safety net of Roosevelt’s New Deal rendered the Poor Farm obsolete. Emma Jane Arey was the last person to move into the Vinalhaven Poor Farm as an “inmate.” She arrived in April 1943 and died the following month.

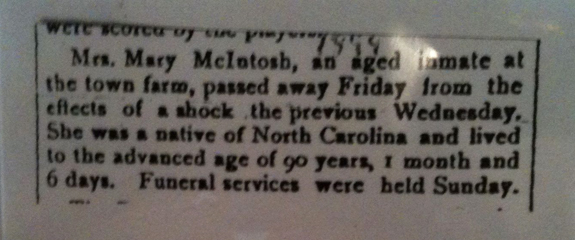

By the time summer people purchased the Poor Farm in the 1950s, it had acquired a reputation for “unearthly visitants” who made a habit of “prowling through the empty rooms” long past midnight. Stories abound, none too exact, about who or what was responsible for the “strange tappings,” with someone named Mary frequently assigned blame. The ledger books reveal that at least two people named Mary lived at the Poor Farm in its early years. Mary Emery, a young girl, arrived with one trunk and clothes in July 1894, but she was taken in by an older brother before she was 14. Mary McIntosh, an old woman, arrived with a feather bed and a rocking chair, in addition to one trunk and clothes; she died at the Poor Farm in February 1899 at the age of 90. It’s hard to imagine why either Mary would want to make things go bump in the night, but the elder Mary’s obituary may hold a clue.

What sort of shock could that aged inmate have experienced at the Poor Farm that would have caused her death a few days later? A lonely Maine winter, a house that received few visitors–if I was inclined towards the gothic, I’d suspect a moral panic of the sort that lurks in The Turn of the Screw. (Henry James’ famous ghost tale was serialized in 1898; alas, the ledger book fails to indicate if the Poor Farm subscribed to Collier’s Weekly.) Beyond my own romantic imaginings, there’s no actual evidence to support this claim, and Central Maine Paranormal Investigations have yet to respond to my inquiries.

Evidence or not, I know people who will tell you their hair stood on end when passing through an upstairs hall and others who will swear they saw an apparition in a bedroom in the night. My own dog has barked emphatically, even ferociously, at what appears to be a dark and empty room. Of course, this could just as easily have been a mouse under the floorboards.

If the Poor Farm is an uncanny kind of place, this has nothing to do with Mary’s ghost. Anthony Vidler has described the architectural uncanny, and the unhomely house, as a critical extension of Freud’s unheimlich, that condition of alienation the strangely familiar frequently produces. But what if a place is the opposite of unhomely? What if a place produces not alienation, but belonging? The Poor Farm is that kind of place.

In 1986 the artist Alison Hildreth purchased the Poor Farm with her husband Horace and transformed the ground floor of the former dormitory into a print studio. Soon, she began renting the Poor Farm to individual artists and arts organizations for residencies and meetings. DesignInquiry held its first gathering at the Poor Farm in 2006, and that’s how I ended up there in 2007.

When I was at the Poor Farm this past summer, we got to talking about its past and its future, and this makes me think now about pentimento, the word Lillian Hellman used for the title of her 2nd volume of memoirs (published in 1973). Early in the book she describes it this way: “old paint on canvas, as it ages, sometimes becomes transparent. When that happens it is possible, in some pictures, to see the original lines…That is called pentimento because the painter ‘repented,’ changed his mind.” For Hellman, pentimento was a way of seeing her life, and then seeing it again: “The paint has aged now and I wanted to see what was there for me once, what is there for me now.”

A building is much like a life, though most, like the Poor Farm, have many painters. In the quarter century the Hildreth’s have owned the Poor Farm, they’ve all left their mark, giving the place a patina of creative accretion, much of it ephemeral, some of it enduring, all of it resonant.

The Poor Farm isn’t haunted; it’s inhabited.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.