Darkness on the Edge of Town 3 November 2012

The darkness wasn’t confined to the edge of town, but there was something startling about seeing it there, at the edge of the island, on the bikeway, in the gloaming. North of 34th Street the lights were on; south of 34th Street they weren’t. At twilight you could still make out the distinctive profile of the darkened street lamps, teardrop luminaires hanging from mast-arm poles (replicas of a 1908 design), stretching down the length of the West Side Highway.

A bit later, and a mile or so inland, where the street wall tends to obscure the sky, the transition from light to dark was more dramatic. Riding down Lower Fifth toward what the wags had already dubbed “SoPo”–as in South of Power–I kept thinking of a scene in The Chronicles of Narnia (Book 3). As the Dawn Treader sails closer and closer to a dark and looming mist, the brightness gives way to grey and then “beyond that again, utter blackness as if they had come to the edge of a moonless and starless night.” In Manhattan, this occurred somewhere below 23rd Street where the car headlights and the pedestrian flashlights created long, wavy streaks, colored arcs against a black background.

Pausing to look back north to where the power was still on, the Empire State Building, framed by so much darkness, seemed taller than usual. Its setbacks lit up in orange and white, the tower was surprisingly reassuring–in that way you suddenly appreciate something you normally take for granted.

Pausing to look back north to where the power was still on, the Empire State Building, framed by so much darkness, seemed taller than usual. Its setbacks lit up in orange and white, the tower was surprisingly reassuring–in that way you suddenly appreciate something you normally take for granted.

I’ll admit to taking the building’s changing color scheme for granted: red, white, and blue for July 4th, etc. I wrongly assumed the orange lights were for Halloween, but they were actually meant to draw attention to the “after Sandy” relief efforts of the Food Bank for New York City.

Turning from the tower to the street, it took a while for your eyes to adjust to the darkness. Eventually, about the same time you realized how pathetically dim your bike headlamp really was, the buildings slowly emerged from the gloom, and you could make out the apartments, the offices, the stores. Here, a really long exposure captures a blank wall and a water tower against the lightless skyline.

Turning from the tower to the street, it took a while for your eyes to adjust to the darkness. Eventually, about the same time you realized how pathetically dim your bike headlamp really was, the buildings slowly emerged from the gloom, and you could make out the apartments, the offices, the stores. Here, a really long exposure captures a blank wall and a water tower against the lightless skyline.

Further downtown, the dark was darkest on the side streets where the traffic and ambient illumination were almost nonexistent. Off Varick Street, close to the Holland Tunnel, which was still closed because of flooding, the high-rise commercial lofts give way to a few isolated blocks of low-rise residences. In row after row, there were no candles flickering, there were no devices glowing. I leaned my bike against a gate and snapped a few pictures. They looked pitch black, but upping the brightness and contrast later on revealed what registered on the camera’s sensors that night: a late federal town house where the windows were as dark and mute as the frames were ghostly and white. Either no one was at home, or they’d all turned in early. I knocked a few times, but the rapping seemed indecent on such a silent street, so I got back on my bike and pedaled home.

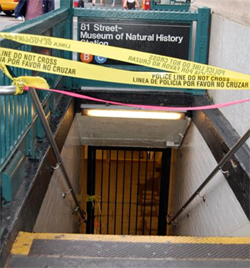

Uptown things were different. Unless you went looking for them, the downed tree limbs in the parks and the river silt washed up by the surge were easy to miss. Walking on Central Park West or Broadway towards the end of the week, only the subway entrances–with old school yellow police tape or info-age electronic services advisories–hinted at the devastation elsewhere.

Uptown things were different. Unless you went looking for them, the downed tree limbs in the parks and the river silt washed up by the surge were easy to miss. Walking on Central Park West or Broadway towards the end of the week, only the subway entrances–with old school yellow police tape or info-age electronic services advisories–hinted at the devastation elsewhere.

At times like these in the city, one turns, inevitably, to E.B. White: “New York is peculiarly constructed to absorb almost anything that comes along…without inflicting the event on its inhabitants so that every event is, in a sense, optional, and the inhabitant is in the happy position of being able to chose his spectacle and so conserve his soul.” In this case E.B. didn’t get it quite right: no one in the unhappy position of living in Lower Manhattan or the Rockaways or Staten Island was choosing his or her spectacle. Elsewhere in the five boroughs you knew what he meant: life went on for the rest of the eight million, at least until they had to get to work.

At times like these in the city, one turns, inevitably, to E.B. White: “New York is peculiarly constructed to absorb almost anything that comes along…without inflicting the event on its inhabitants so that every event is, in a sense, optional, and the inhabitant is in the happy position of being able to chose his spectacle and so conserve his soul.” In this case E.B. didn’t get it quite right: no one in the unhappy position of living in Lower Manhattan or the Rockaways or Staten Island was choosing his or her spectacle. Elsewhere in the five boroughs you knew what he meant: life went on for the rest of the eight million, at least until they had to get to work.

Reading Here is New York is generally balm for the soul, but this week it was strangely discomforting, and White’s celebration of the city’s “patience and grit” did little to relieve the queasiness brought on by observations like this: “By rights New York should have destroyed itself long ago, from panic or fire or rioting or failure of some vital supply line in its circulatory system or from some deep labyrinthine short circuit…It should have been overwhelmed by the sea that licks at it on every side.”

Post-storm, it is prudent to stay with the essay all the way to the end because there, in the last few paragraphs, White brings you back around. He doesn’t finish on a particularly happy note: writing in 1949, with WWII still fresh in his memory, White identifies a subtle change in the city–the recognition that New York is destructible. “The intimation of mortality is part of New York now,” he wrote then, in a simple sentence that still resonates a half century on. White didn’t lament this new reality, and neither should we. Instead, he seized it as an opportunity to reflect upon the city’s value to him individually, and to the culture as a whole. New York, White concludes, is a “mischievous and marvelous monument which not to look upon would be like death.” Riding through the darkness as the city regained its bearings, I knew exactly what he meant.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.