Penn Station, for the record 17 April 2013

Last week, the New York City Planning Commission held a public hearing to decide the future Pennsylvania Station. At issue, as Michael Kimmelman has explained thoroughly in the New York Times, is whether to allow Madison Square Garden to continue to operate an arena on the site it has occupied since 1968—squarely on top of Pennsylvania Station. My friend and former student, Omar Toro-Vaca (who works for Vishan Chakrabarti and SHoP Architects), urged me to testify at the hearing to add my voice to the public record. Since I was already scheduled to be in Buffalo, attending the annual conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Omar agreed to read this testimony on my behalf.

Chairwoman Burden, Members of the Commission, and Distinguished Guests, my name is Gabrielle Esperdy and I am speaking to you today as a resident of Manhattan, a citizen of the metropolis, and a commuter to New Jersey. In each case, my perspective is colored by my profession: for I am also an architectural and urban historian and a professor of architecture who studies the dynamics of metropolitan transformation in the 20th and 21st centuries by analyzing changing patterns of form and meaning in our buildings and landscapes. As a student of this great city’s past and an active participant in its future, I urge you to deny a renewal in perpetuity of the special permit issued to the Madison Square Garden Company to operate its arena atop Pennsylvania Station.

The Commission has before it a grave decision—it can choose to rectify one of the great tragedies of American urbanism by allowing the redevelopment of Penn Station for this millennium, or it can choose to be on the wrong side of history and allow the nation’s busiest transportation hub to exist as the degraded sub-basement of a venue whose urban presence (regardless of its institutional contribution to the city’s cultural life) bespeaks the outsized mediocrity of an ignoble moment in New York’s past—a moment that far too many people mistook for the twilight of civicism and the fall of the public realm.

The Commission has before it a grave decision—it can choose to rectify one of the great tragedies of American urbanism by allowing the redevelopment of Penn Station for this millennium, or it can choose to be on the wrong side of history and allow the nation’s busiest transportation hub to exist as the degraded sub-basement of a venue whose urban presence (regardless of its institutional contribution to the city’s cultural life) bespeaks the outsized mediocrity of an ignoble moment in New York’s past—a moment that far too many people mistook for the twilight of civicism and the fall of the public realm.

The irony, as we all know, is that the infrastructure of the earlier station is punishingly intact. While it once functioned majestically as what Lewis Mumford called a “gravity flow system,” the gravity doesn’t flow the way it used to—there are simply too many of us now, jammed into concourses and crowded onto platforms that were designed more than a century ago. And while a few of us may smile nostalgically as we descend one of McKim’s original cantilevered staircases down to the tracks, most of us—pressed on all sides by our fellow commuters— are too cranky to notice the vestigial graciousness of this descent, and how different it is from the claustrophobia that typifies track access elsewhere in the station, where we are forced to descend what seem like back office fire stairs rather than grand spaces of intentional circulation. But even if we’ve noticed the difference, we aren’t surprised—because, to paraphrase Vincent Scully, the great Yale historian, we’ve become used to scuttling through Penn Station like a rat.

The irony, as we all know, is that the infrastructure of the earlier station is punishingly intact. While it once functioned majestically as what Lewis Mumford called a “gravity flow system,” the gravity doesn’t flow the way it used to—there are simply too many of us now, jammed into concourses and crowded onto platforms that were designed more than a century ago. And while a few of us may smile nostalgically as we descend one of McKim’s original cantilevered staircases down to the tracks, most of us—pressed on all sides by our fellow commuters— are too cranky to notice the vestigial graciousness of this descent, and how different it is from the claustrophobia that typifies track access elsewhere in the station, where we are forced to descend what seem like back office fire stairs rather than grand spaces of intentional circulation. But even if we’ve noticed the difference, we aren’t surprised—because, to paraphrase Vincent Scully, the great Yale historian, we’ve become used to scuttling through Penn Station like a rat.

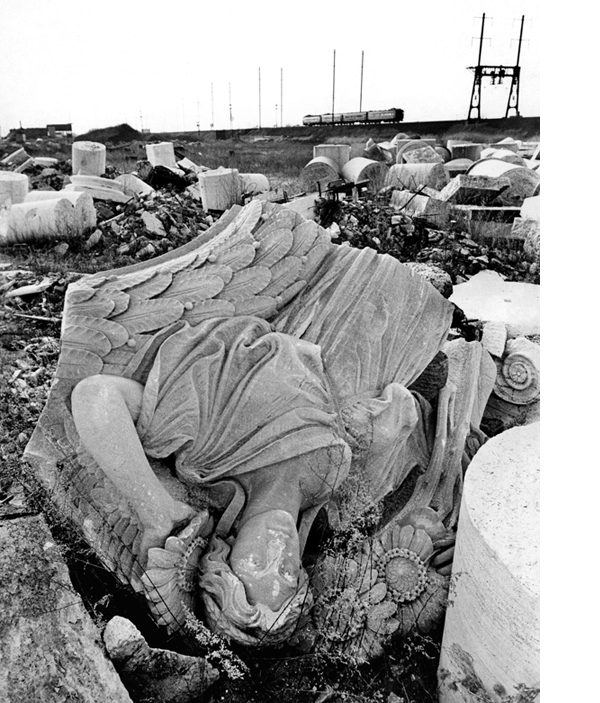

I’ve been scuttling like that myself for more than a decade. And in the years I’ve commuted between Penn Station and Newark not once, as I’ve looked out the window on the other side of the Hudson tunnels, have I failed to think about all that fine Tennessee marble sinking deeper and deeper into the muck of the Meadowlands. There is a tendency these days to romanticize ruins, and that’s just fine, as long as they’re not part of your everyday life and your everyday commute. Let me paraphrase Scully again: it’s time we gave all citizens of this metropolis the opportunity to once again enter New York like a god.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.