Prelude: May 2006 1 February 2013

What follows is probably too autobiographical, and certainly more bloggy than usual for this blog, but I hate to waste a piece of perfectly good writing–good, not necessarily in terms of quality, but meaning a text already written, never distributed, hanging out in an obscure file folder taking up space (if 105KB counts as taking up space). And good, too, in the way it anticipates what would become American Road Trip. Reading the text now, almost seven years after it was written, I’m struck by the degree to which ubiquitous mobile technology has changed the way we see, experience, and remember the world we encounter in our everyday lives. Perhaps that’s a banal observation in this iPhone era, but banalities intrigue me as much as extraordinaries, and that’s kind of the purpose of what I’m trying to do here on this site.

[NB: as will be clear below, I didn’t have a camera; all images used under Creative Commons license.]

Walking up Sixth Avenue on a nearly perfect spring morning, my friend and I were headed to the Donald Judd show at Christies, but we were talking about the Guggenheim.

She observed that maybe Wright’s spiral worked pretty well after all: at least for monographic shows (David Smith: a Centennial had just closed), the unwinding layers give you an almost archeological view of an artist’s work, allowing you to probe/glance backwards and forwards in time and space as you look across the rotunda at the various “strata” on display.

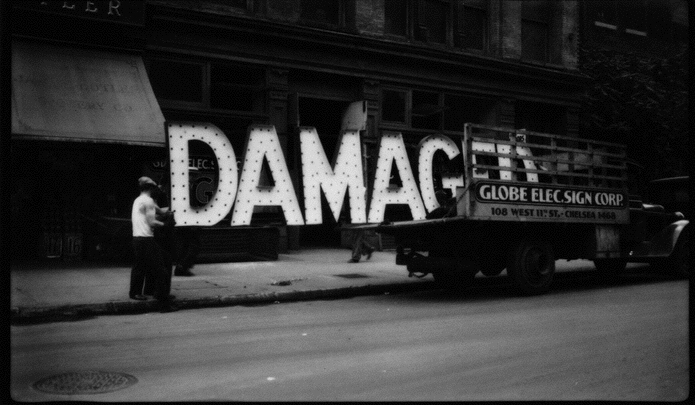

I shifted the conversation to the building’s exterior and asked if she had noticed the mistake on the façade, now in plain sight because of the current renovation. With layers of paint and concrete removed one can see that the craftsman carving the letters on the façade had initially started too high up, rather than at the lower edge as Wright had specified in his drawings.

Thus, the “T” generally visible in “The” has a ghost just above it—somewhere between a palimpsest and a pentimento, I suppose—bearing witness to fact that the building was made by hand (and thus subject to human error), despite the machinist precision of its forms.

I told my friend that I wanted to take a picture of the ghost letter, but that I keep forgetting. She observed that there are often things she sees on the street that she wishes she could record in some way in order to use them at a later date. We talked about the value of having a camera in one’s mobile phone to be used for such a purpose.

I mentioned that I had been inspired to start walking around with a camera after seeing a Walker Evans show at the Met some years ago, but this had not amounted to anything. She talked about what she might do with such images once she had them collected, perhaps assemble them in some accessible way and then use them as a reference point or inspiration. A thing glanced in the physical world becomes a memory connected to its original experience; almost simultaneously, it becomes an image to be deployed, perhaps in an entirely different context, perhaps entirely disassociated from the original experience. My friend is an architect and a designer; she might use the thing-memory-image in a formal exploration of color or texture or scale, contrasted or juxtaposed, for a project on paper or realized in built form. But I am a historian and a writer. How will I use the thing-memory-image?

Here is a clue. My friend lent me a book called Chasing the Perfect by Natalia Ilyin; I took copious notes. Among the many things the book made me realize (too many to mention here) is that in pursuing my chosen profession—getting the Ph.D., getting the tenure-track job, getting tenure—I have too often forgotten my vocation. I have forgotten what propelled me into architecture in the first place—not the practice of architectural design (I bailed from my first and only architecture studio after four weeks), but the practice of architectural writing. Now, I spend a good deal of my time outside of the classroom engaged in architectural writing, but I’m talking about real pleasure-of-the-text writing, writing that isn’t intended for a peer-reviewed journal or an academic press, writing that explores an idea for its own sake without concern for the validity of an argument or the burden of evidence. And this is where the thing-memory-image comes in: having collected these for as many of my forty years as I can remember, I have yet to make use of them in my practice. What follows is my first attempt to write into that void.

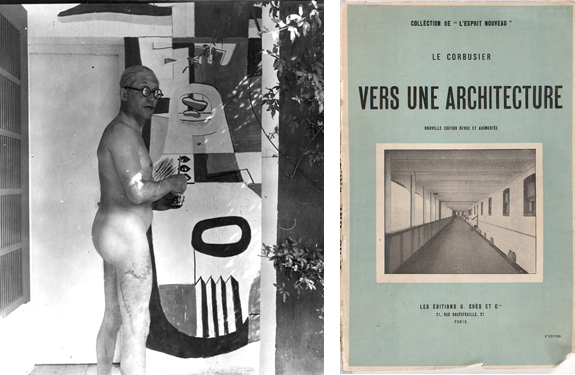

Here is another clue (or maybe a rationalization of recurring feelings of inadequacy at being an architecture professor who doesn’t teach design). Le Corbusier pursued a double métier (painting + architecture) his entire life, but given his corpus of written work, it might be more accurate to say he pursued a triple métier. For Rem, research, writing and design are parallel tracks of his architectural practice (hence OMA spawned AMO). What follows, then, is writing towards architecture and writing as architecture. Hopefully, it is the first of many minor texts to come.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.