I could live here 25 February 2011

An article in the New York Times about Derek Diedricken’s Gypsy Junker microshelter reminded me how much I like a hut myself. I didn’t really need reminding–I live with a large Scott Peterman photograph of an ice fishing hut in Maine (Sabbath Day Lake III, 1998)–but the article did get me thinking about how long huts have been an object of affection.

I’ve never actually had a hut to dwell in, but when I was a kid I thought it would be cool to turn the rotting garden shed in our back yard in Chestnut Hill into a room of my own. (That I already had a room of my own, that, in fact, I had always had a room of my own, never obtruded upon this fantasy.) That shed was a rough six-foot cube of corrugated sheet metal, just big enough for a riding mower, a wheelbarrow, and a couple of rakes. The walls were white; the doors were green; the floor was plywood. The shed was already there when we moved to the house in 1974. It’s rusty musty state undoubtedly increased its appeal.

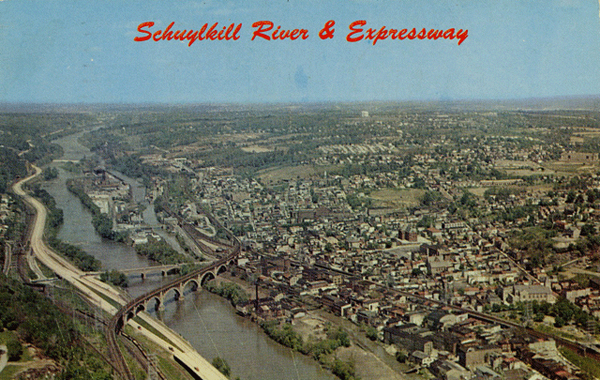

In high school I was fixated on a different shed; this one was also sheet metal but it must have been made of sturdier stuff, too, because it was raised a story off the ground, possibly above the railroad tracks, somewhere in Manayunk, close to the Schuykill and the old canal.

In the early eighties, Manayunk was still years away from gentrification and the shed was one small element in a much larger drosscape of abandoned factories, chain link fences, barbed wire, and hub caps. I wanted to live in that shed, too. I’m guessing the appeal there was the promise of a room with a view–post-industrial landscapes having a romantic quality even then.

In the early eighties, Manayunk was still years away from gentrification and the shed was one small element in a much larger drosscape of abandoned factories, chain link fences, barbed wire, and hub caps. I wanted to live in that shed, too. I’m guessing the appeal there was the promise of a room with a view–post-industrial landscapes having a romantic quality even then.

A few weeks ago, while visiting Thomas Edison’s Research Laboratory in West Orange, I decided that a room without a view would be good. Wandering around the complex with my colleague Matt Burgermaster (who’s been researching Edison’s concrete building patents), I was particularly taken with Vault 33.

Originally used to store molds for Edison’s phonographic cylinders, it’s a windowless concrete box, utterly plain but for an entablature-like cornice. This vestigially classical detail on an otherwise utilitarian structure is as charming as it is silly. Henry Hudson Holly was responsible for the design of a number of buildings on the site and it wouldn’t surprise me if this picturesque flourish was his doing. I could live with the cornice, but whether the the sensory deprivation quality of the interior would get to me, I’ll never know. Vault 33 is closed to the public because it’s still used to store a part of Edison’s archive.

Originally used to store molds for Edison’s phonographic cylinders, it’s a windowless concrete box, utterly plain but for an entablature-like cornice. This vestigially classical detail on an otherwise utilitarian structure is as charming as it is silly. Henry Hudson Holly was responsible for the design of a number of buildings on the site and it wouldn’t surprise me if this picturesque flourish was his doing. I could live with the cornice, but whether the the sensory deprivation quality of the interior would get to me, I’ll never know. Vault 33 is closed to the public because it’s still used to store a part of Edison’s archive.

So what is it about huts? They are “humble and iconic, insignificant and portentous, ephemeral and enduring.” Or so I thought back in 2003 when I did some research on them for an exhibition called Cabin Fever at the Ox-Bow School of the Arts. What I produced was a highly selective, idiosyncratically episodic architectural and cultural history of the hut. In other words, content perfect for posting here.

Coming soon: The Hut, parts i, ii, iii.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.