Inhabiting the Poor Farm 1 October 2012 No Comments

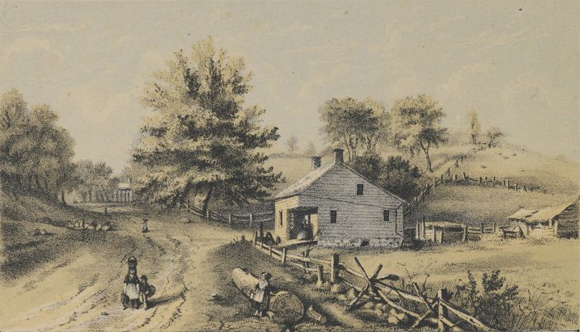

They say the place is haunted. And when you encounter the Vinalhaven Poor Farm for the first time, it’s easy to understand why. It’s a rambling sort of building, with long halls and odd staircases, with forgotten rooms and creaking doors that won’t stay closed. The oldest part of the house is a traditional Cape with an attached ell, both built by James Smith (or was it John Smith) in the 1830s.

More precisely, the house is a “full Cape,” with an entrance facade consisting of two windows flanking both sides of a centrally-placed door. This opens onto a small vestibule dominated by tight curving stairs that lead up to modest bedrooms under the eaves–just the sort that could be occupied by spirits. Typical of this part of New England, the one-story ell linked the house to the barn to create what’s called a connected farm, a useful arrangement for tending to the animals when the weather was less than agreeable.

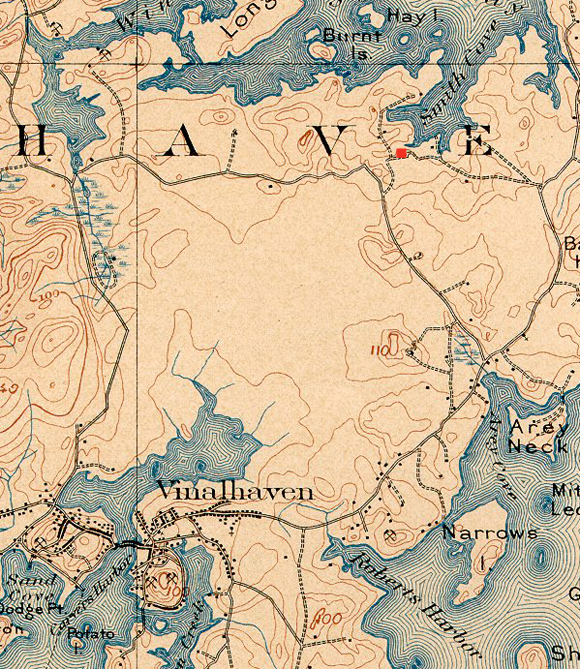

According to the local records, at least four generations of the Smith family farmed this eastern shore of Vinalhaven island, from the middle of the eighteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth, long enough for them to lend their name to the cove you still see from the house today.

Smiths remained on the land even after the Town of Vinalhaven purchase 100 acres and the connected farm buildings for $900 to use as a poor farm: Eban G. Smith and his unnamed wife served as the farm’s keepers when the first inmates arrived in July of 1894. They ran the place as a subsistence homestead, with a large vegetable garden, a couple of cows, some pigs, and chickens who seemed to have had the run of the place.

Smith, and the keepers who followed (Misters Spears, Morton, Hall, and Bunker), kept a strict accounting of the room and board he and his wife provided, noting in a ledger book (in the collection of the Vinalhaven Historical Society) all living expenses charged against the residents: cough medicine, flannel, yarn, work boots, pipes, matches, tobacco, etc. The folks who used these supplies were mostly local: widows, orphans, and indigent farmers and fishermen native to the island, or from nearby on the mainland, but the records indicate that Italians and Swedes were also at the Poor Farm in its early years.

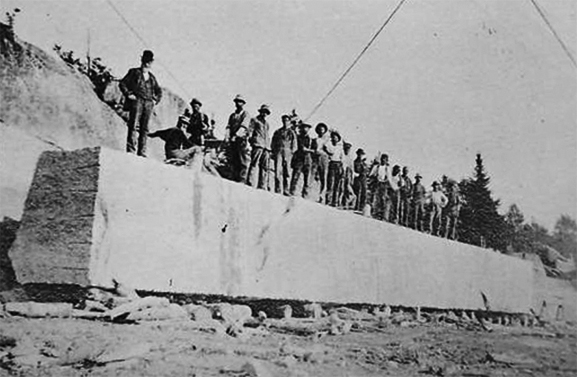

Having come to the island to work as stonecutters in Vinalhaven’s thriving granite quarries, they also had to endure seasonal layoffs and the increased mechanization of the industry, which probably explains why some of them ended up at the Poor Farm.

Before 1900, the town appropriated an additional $600 for “enlarging the house and making room to accommodate more inmates.” The original connected barn was replaced with a tall dormitory close to the road. With two-full stories plus an attic rising under a single broad gable, the dormitory was a large clapboard shed divided into small rooms on either side of a center hall.

This new wing gave the Poor Farm a more institutional appearance, but the added space proved a worthwhile investment after the stock market crash of 1929. The ledger books from the 1930s show that there were more Vinalhaven residents living at the Poor Farm during the Great Depression than at any other time in its existence. Some Poor Farmers moved in and out during this period, leaving if they found work (in island quarries or mainland canning factories), and returning when they were unemployed. Slowly, though, throughout the decade, the social safety net of Roosevelt’s New Deal rendered the Poor Farm obsolete. Emma Jane Arey was the last person to move into the Vinalhaven Poor Farm as an “inmate.” She arrived in April 1943 and died the following month.

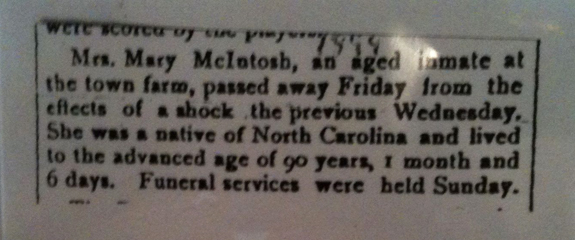

By the time summer people purchased the Poor Farm in the 1950s, it had acquired a reputation for “unearthly visitants” who made a habit of “prowling through the empty rooms” long past midnight. Stories abound, none too exact, about who or what was responsible for the “strange tappings,” with someone named Mary frequently assigned blame. The ledger books reveal that at least two people named Mary lived at the Poor Farm in its early years. Mary Emery, a young girl, arrived with one trunk and clothes in July 1894, but she was taken in by an older brother before she was 14. Mary McIntosh, an old woman, arrived with a feather bed and a rocking chair, in addition to one trunk and clothes; she died at the Poor Farm in February 1899 at the age of 90. It’s hard to imagine why either Mary would want to make things go bump in the night, but the elder Mary’s obituary may hold a clue.

What sort of shock could that aged inmate have experienced at the Poor Farm that would have caused her death a few days later? A lonely Maine winter, a house that received few visitors–if I was inclined towards the gothic, I’d suspect a moral panic of the sort that lurks in The Turn of the Screw. (Henry James’ famous ghost tale was serialized in 1898; alas, the ledger book fails to indicate if the Poor Farm subscribed to Collier’s Weekly.) Beyond my own romantic imaginings, there’s no actual evidence to support this claim, and Central Maine Paranormal Investigations have yet to respond to my inquiries.

Evidence or not, I know people who will tell you their hair stood on end when passing through an upstairs hall and others who will swear they saw an apparition in a bedroom in the night. My own dog has barked emphatically, even ferociously, at what appears to be a dark and empty room. Of course, this could just as easily have been a mouse under the floorboards.

If the Poor Farm is an uncanny kind of place, this has nothing to do with Mary’s ghost. Anthony Vidler has described the architectural uncanny, and the unhomely house, as a critical extension of Freud’s unheimlich, that condition of alienation the strangely familiar frequently produces. But what if a place is the opposite of unhomely? What if a place produces not alienation, but belonging? The Poor Farm is that kind of place.

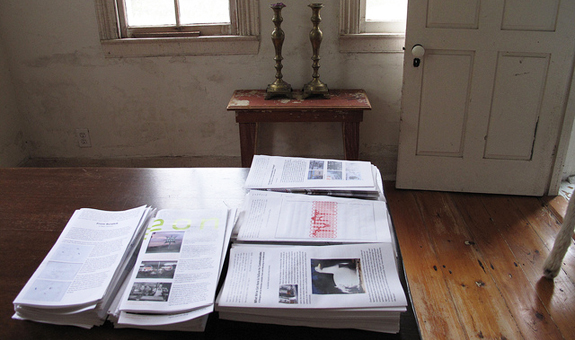

In 1986 the artist Alison Hildreth purchased the Poor Farm with her husband Horace and transformed the ground floor of the former dormitory into a print studio. Soon, she began renting the Poor Farm to individual artists and arts organizations for residencies and meetings. DesignInquiry held its first gathering at the Poor Farm in 2006, and that’s how I ended up there in 2007.

When I was at the Poor Farm this past summer, we got to talking about its past and its future, and this makes me think now about pentimento, the word Lillian Hellman used for the title of her 2nd volume of memoirs (published in 1973). Early in the book she describes it this way: “old paint on canvas, as it ages, sometimes becomes transparent. When that happens it is possible, in some pictures, to see the original lines…That is called pentimento because the painter ‘repented,’ changed his mind.” For Hellman, pentimento was a way of seeing her life, and then seeing it again: “The paint has aged now and I wanted to see what was there for me once, what is there for me now.”

A building is much like a life, though most, like the Poor Farm, have many painters. In the quarter century the Hildreth’s have owned the Poor Farm, they’ve all left their mark, giving the place a patina of creative accretion, much of it ephemeral, some of it enduring, all of it resonant.

The Poor Farm isn’t haunted; it’s inhabited.

Outside Exeter Library 6 July 2012 No Comments

In Megalopolis, Jean Gottmann called the I-95 corridor the “Main Street of the Nation” to convey its significance to the vast conurbation of the northeastern U.S. That’s a useful way of thinking about the longest north-south interstate in the country, its nearly 2,000 miles connecting major population centers and an almost continuous fabric of sprawl. But we all know that Main Streets and Interstates are very different sorts of roads–perceptually, symbolically, and physically. Main Streets go through places; Interstates, except for the notorious ones that gutted urban centers in the 1960s, go around places. This is certainly true of the stretch of I-95 that I know best, between Washington, D.C. and Bangor, Maine. North of New York, once the road cuts through Washington Heights and the South Bronx, it goes around Stamford, around New Haven, around Providence, around Boston, around Portsmouth, around Portland.

If the town is big enough and the by-pass is proximate enough, you can discern the skyline from the highway. In Stamford and New Haven, buildings grew up around the interstate–Roche-Dinkeloo’s Knights of Columbus being the most thrilling example, or the most appalling, depending on how you feel about Brutalism.

In smaller places, the towns are invisible from the highway, but for hints provided by the signage overhead, as at Exit 4 in New Hampshire, which discreetly directs drivers to the Portsmouth Traffic Circle. If you’re not paying attention, you might miss New Hampshire entirely. Of all the states I-95 passes through, NH has the least mileage–only 16 miles between Massachusetts and Maine. That gives you about 15 minutes to experience the granite state in all its live-free-or-die glory, but on 95 from the North Shore to Piscataqua River there is precious little that makes an impression, notwithstanding the irresistible allure of tax free booze at the State Liquor Outlet.

This time of year, I always look forward to pulling off at Store #76 near (not in) Hampton Falls to stretch my legs, let the dog out of the car, and lay in a supply of libations for DesignInquiry’s annual Vinalhaven gathering. I also look forward to savoring the aesthetic absurdities of the big red barn by the side of the highway, complete with fake cupolas, faux sliding doors, and vinyl clapboards.

I’d like to believe the New Hampshire Liquor Commission chose this homage to the architecture of New England agriculture as a way of acknowledging the historical importance of farmer bootleggers during Prohibition, but I know better–those vestigial elements stopped signifying decades ago. Though maybe they still have some vague associations with country folk and country manners, the friendliness of buying booze in a barn serving to assuage the guilt of out-of-town scofflaws transporting whiskey and wine across state lines.

I didn’t spend much time contemplating this interpretation during my most recent trip to Store #76 because for once I intended to actually see something of New Hampshire beyond the I-95 corridor, briefly leaving the “Main Street of the Nation” for an actual Main Street. Somehow though, whether we were overwhelmed by the wine-in-a-box options or distracted by the sampler gift packs of tequila and scotch, by the time we pulled back onto the highway for the six mile drive to Exeter it was later than I hoped.

As High Street gave way to Main Street (via Water) Exeter revealed a downtown of tidy commercial buildings and upscale storefronts. Other than a sweet little beaux-arts bandshell (built 1916), there was nothing remarkable about the place, which is perhaps what made it so remarkable–an exceptionally well-preserved urban fabric from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Residential neighborhoods are scattered about the commercial core, containing more than a few 17th and 18th century houses. This isn’t surprising since Exeter was founded in 1638, by religious exiles from Massachusetts. Among them was Edward Gilman, who came up from Hingham, where the Old Ship Meeting House is located.

A visit to the Old Ship, the nation’s oldest house of worship in continuous use, was last summer’s off I-95 adventure en route down east. Attempting to go inside the meeting house last June, though it was clearly closed for renovations, we managed to set off a motion detector alarm and had to hide in the burying ground until the cops left. However undignified this may have been, it afforded an excellent vantage point for photographing the building in the late afternoon.

Edward Gilman of Hingham moved up to Exeter several decades before the Old Ship Meeting House was built in 1681. By then, his children and grandchildren had become prominent in Exeter as merchants and shipbuilders. A century later, in 1781, they had sufficient wealth to endow the newly established Phillips Exeter Academy and to donate a large tract of land to serve as its campus. It was the academy that brought us to Exeter.

The 19 buildings Ralph Adams Cram designed on the campus circa 1914 have an undeniable appeal–not only because he was a native of Hampton Falls, location of New Hampshire Liquor Outlet #76, but because the classicism of the academy’s colonial revival structures is not what you’d expect from the king of collegiate gothic. Still, there’s no use pretending that we were there to see anything but the library.

The 19 buildings Ralph Adams Cram designed on the campus circa 1914 have an undeniable appeal–not only because he was a native of Hampton Falls, location of New Hampshire Liquor Outlet #76, but because the classicism of the academy’s colonial revival structures is not what you’d expect from the king of collegiate gothic. Still, there’s no use pretending that we were there to see anything but the library.

The Exeter Library is so iconic it’s the kind of building that haunts your dreams, a perfect embodiment of Lou Kahn’s semi-mystical utterances about space, form, and meaning. “Architecture comes from the making of a room,” Kahn declared in 1971, the year the library was finished, in what seems like an apt description of the building’s great central space, a raised, multi-level atrium of platonic voids and concrete geometries serving as a symbolic gathering space for a learning community.

Or so I’m told. By the time we got to Exeter in the late afternoon, the library was closed. Instead of the expansive money shot on the left (courtesy Daderot on Wikimedia Commons), I got the occluded off-kilter shot on the right. But if, in being forced to peer through glass entry doors, I was denied the breadth of the atrium, I got something just as good, and just as important to Kahn’s work: a shift in focal distance from the communal to the individual, from the monumental to the ceremonial. Even from the outside, this is evident in the gently curving concrete stairs that Kahn clad in travertine to mediate human engagement with the building.

Or so I’m told. By the time we got to Exeter in the late afternoon, the library was closed. Instead of the expansive money shot on the left (courtesy Daderot on Wikimedia Commons), I got the occluded off-kilter shot on the right. But if, in being forced to peer through glass entry doors, I was denied the breadth of the atrium, I got something just as good, and just as important to Kahn’s work: a shift in focal distance from the communal to the individual, from the monumental to the ceremonial. Even from the outside, this is evident in the gently curving concrete stairs that Kahn clad in travertine to mediate human engagement with the building.

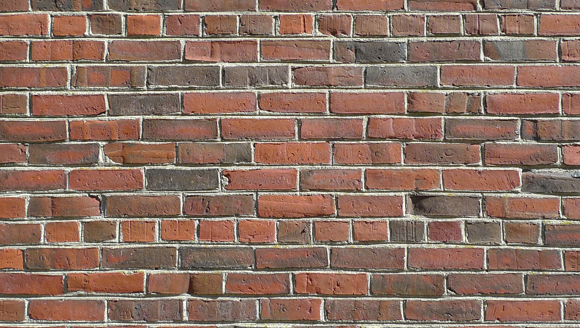

One notices the meeting of concrete and travertine because Kahn, characteristically, used a limited palette of materials that rendered each one more powerful, and nowhere is this clearer than in the library’s load-bearing brick facades. Locked out of the library, we had ample time to ponder them in detail.

Chamfered corners reveal the structural conceit of the self-supporting walls; granite sills are deep enough for comfortable sitting; segmental arches have a subtle modulation; piers grow more slender and bays grow wider as the load lightens up the facade; inset teak panels look like spandrels but are actually built-in study carrels.

Twenty years ago Vincent Scully changed the discourse about Kahn by placing his work in the context of “the ruins of Rome.” Walking around the Exeter Library the evocation makes sense, given the muscular strength of the brick walls and shadowy spareness of the covered walkways.

But as I moved from one passageway to another, I couldn’t help wondering if I’d have been thinking of the Markets of Trajan without Scully’s prompt, because up here in New England all that brick could just as easily conjure ruins closer to home–in Lowell, in Manchester, and even in Exeter itself. Between 1901 and 1965, Peter and Alfred Eno supplied bricks for buildings throughout New Hampshire, including many on the Phillips Exeter campus, from a manufacturing plant on the southwest edge of town. When the company folded in the mid-60s, the school purchased its entire inventory of 2 million bricks and required their use for the new library and the adjoining Elm Street Dining Hall, also designed by Kahn.

[The latter building, an oddly effecting composition of archetypal forms, instantly evokes Venturi’s work from the same period (think Mother’s House and Fire Station No. 4) along with a heavy dose of Aldo Rossi and Giorgio de Chirico. Long overshadowed by the library, the Dining Hall is discussed in an excellent 2004 Future Anterior article by William Richards: “Razing the Exeter Dining Hall: Pros and Kahns.”]

The library’s exterior consists of 420,000 waterstruck Eno bricks, laid in a common bond with a header course every eighth row. However accurate that straightforward description (and one wonders who counted the bricks), it does not come close to capturing the actual quality of the exterior of the Exeter library.

Waterstruck bricks are made of very soft wet clay packed into moulds prepared with water and sodium silicate. As the wet bricks are turned out of their moulds the dragging effect leaves its trace on four sides. During the firing process, those drag marks are transformed into a patina whose texture and color have an astonishing variety, depending on the swiftness of mould pull and, especially, on the brick’s location in the kiln.

From a distance the library facade appears to be a uniform surface of red brick, from close-up you realize it’s the opposite–a hearty mottle of reds, browns, and blacks, of gashes, perforations, and dings. The variety of color and texture was even more pronounced in the late afternoon light, and with nothing to contemplate except the facade of the closed library, we began to take in each variation and every irregularity.

The culled bricks, whose use Kahn must have specified, were the most moving. Melted during the firing process, such bricks were generally rejected as imperfect, but at Exeter, the more severe the distortion the more the culled brick enlivened the facade in a sculptural way, giving it an enticing tactility.

There is a parallel in the effect Alvar Aalto created with clinker brick on the Baker Dorm at MIT (1937-40), but in Cambridge the tweedy irregularity of the bricks extends to the entirety of the facade. In Exeter, by contrast, the culled bricks pop out of the surface at such unexpected moments that after awhile looking at the masonry makes you giddy. That’s when you realize you’ve started to fondle the wall.

“What do you want, Brick?” Kahn famously asked. Supposedly the brick replied “I like an arch,” but on a warm summer afternoon in Exeter, the brick might have been satisfied with something less complicated. We certainly were.

Tents and Tarmac 3 June 2012 No Comments

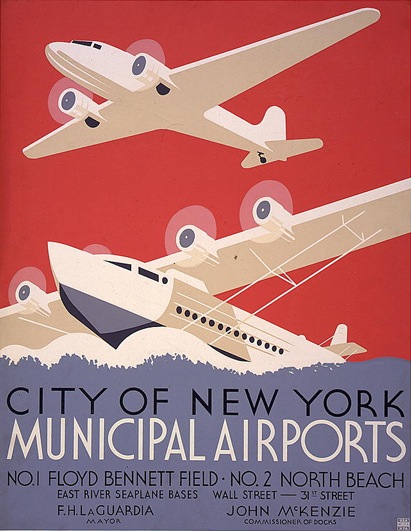

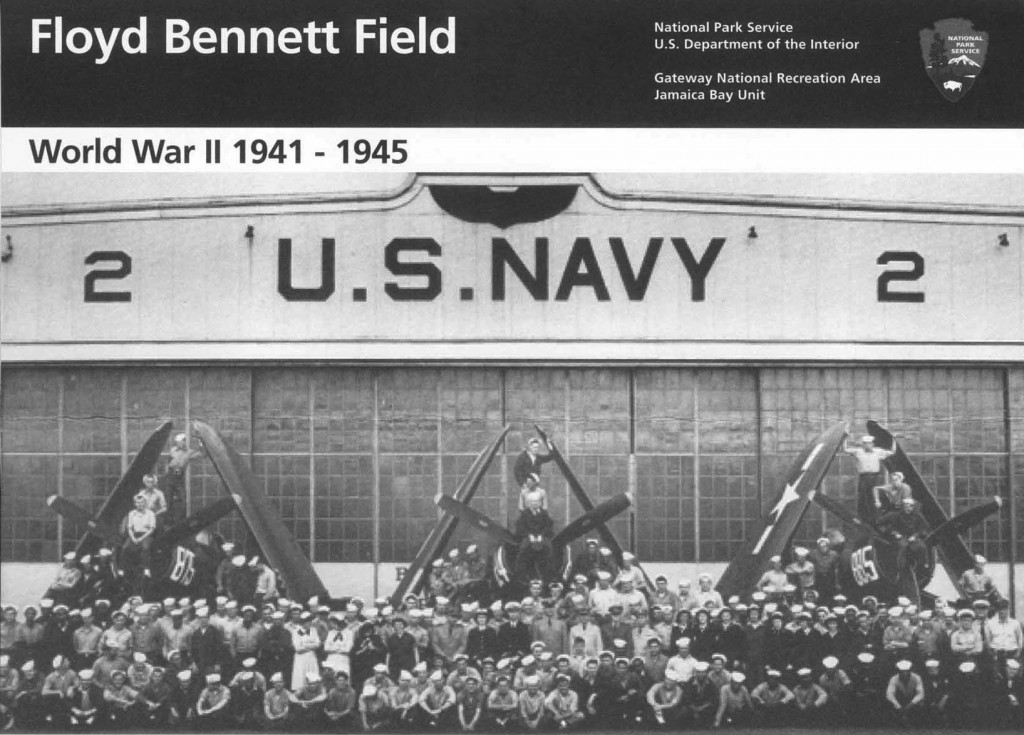

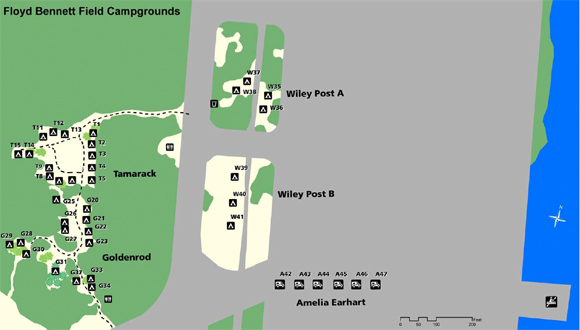

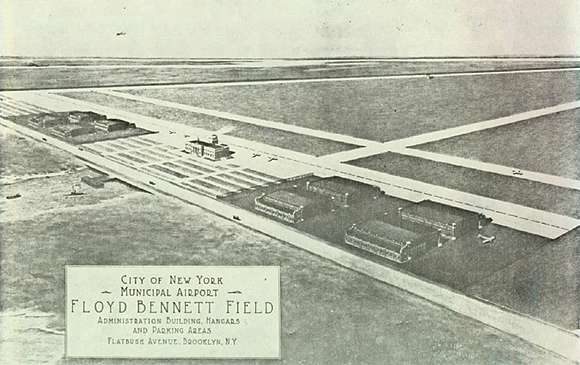

I’ve been contemplating the extremities of Flatbush Avenue because recently I spent a couple of days at Floyd Bennett Field, just off the road’s southern terminus, the last exit before the bridge to the Rockaways. Actually, I spent a couple of nights at Floyd Bennett Field, too.

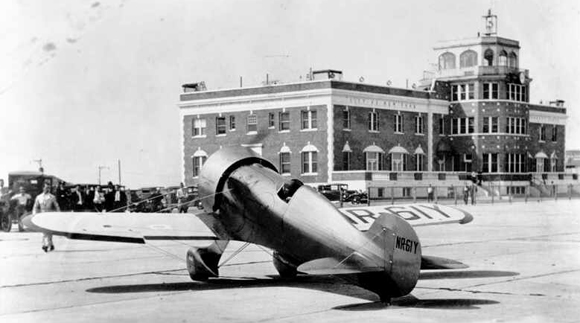

Not because I have a particular passion for aviation, though I’ll admit to watching planes take off from Newark while eating Swedish meatballs at the IKEA in Elizabeth. Not because New York City’s Municipal Airport No. 1 has considerable urban and architectural appeal–concrete runways, art deco hangars, WPA murals. Not even because visiting what is now part of the Gateway National Recreation Area meant I’d be able to add a few more of those Vignelli-designed National Park Service brochures to my collection.

Compelling reasons, to be sure, but not prime motivations. I spent two days and two nights at Floyd Bennett Field because I was camping.

Now, I’m no stranger to roughing it in the city: slept on a sidewalk near the Delacorte to get tickets to the Mike Nichols/Tom Stoppard production of Chekov’s The Seagull with Meryl Streep; relieved myself behind a bush on a traffic island in the shadow of the Williamsburg Savings Bank while running the marathon. Compared to being out there at Floyd Bennett Field, though, all that was just quotidian urban adventuring.

This was proper camping–tents, sleeping bags, pit toilets, flashlights, solar showers, non-potable water.

Open fires, s’mores, even campfire songs–if a Donna Summer im memoriam playlist on an iPhone counts.

This was camping like it’s done in the Adirondacks or the Badlands or Yellowstone. Except we were in New York City, in Brooklyn, off Flatbush, at an airfield, by a runway.

There were no coyotes or bears, but some wily raccoons helped themselves to our baked goods. There were no mountains or canyons, but the 747s out of JFK were close enough to make out the airline logos. There were no ancient petraglyphs or abandoned homesteads on the hiking trails, but we did find evidence of earlier inhabitation: a lonely fire hydrant slowly consumed by the returning grasslands.

And that’s how it should be, because you don’t go to Floyd Bennett Field for the nature itself–you go to witness how humans have transformed the nature, turning the wetlands of Dead Horse Bay and Barren Island into a Dutch agricultural village, then a noxious industrial settlement of rendering plants and fish oil factories, then an airport built on millions of cubic yards of landfill.

Though the airport opened to great fanfare in 1931, and played an important role in aviation history, by the 60s it was obsolete. It was too far away from the city’s population centers for commercial viability and had trouble competing with Newark Airport from the beginning. World War II gave it new life as a Naval Air Station but once North Beach/LaGuardia and Idewild/JFK came online, Floyd Bennett Field’s days were numbered. The Coast Guard operated an air station here until the late 80s and the NYPD still has an active helicopter base on site, but the only fixed-wing craft flying at FBF now are remote-controlled miniatures. That’s sort of OK because it leaves the runways free for other uses.

Walking along those runways, which range from 3,000 to 7,000 feet in length, is the closest I’ve ever come to finding big sky country in NYC.

This effect is intensified if you lay down on the tarmac.

And then there are the buildings. The terminal, freshly restored as the Ryan Visitor Center, is lovely, though its interpretive displays are hardly state-of-the art (the newsreels, however, are groovy). Outside, it’s a chipper Georgian revival pile of red brick and concrete (well, cast stone, concrete’s putting-on-airs cousin) that dates to 1930 and tops out with a winged globe on the parapet above the entrance.

Out back, the neo-colonial air traffic control tower, designed by one Hugh McLaughlin of the Department of Docks, happily conflates historicism and high tech.

This was even more obvious before the Navy renovated it in the 40s. Are those really keystones above the arched plate glass windows?

The control tower is so weird and American it’s like a missing chapter from Delirious New York. The skyscraper wasn’t the only way to conquer what Koolhaas called “the frontier of the sky.”

In 2012, though, the hangars are the real attraction.

Four of the hangars closest to Flatbush (to the left in this period rendering) house a recreation concession called Aviator Sports, a place with such a before-Brooklyn-was-hip-old-school-outer-borough vibe that it’s got an airport version of the Fremont Street Experience inside: “the historic aviation-themed entryway, welcome center, and thoroughfare.” I’m not sure why you need an aviation theme at an actual aviation site, but there’s much I don’t understand about marketing.

We didn’t venture in, preferring the authenticity of Hangar B, which is closer to the campgrounds anyway, straight down Runway 24 on the edge of Jamaica Bay. Built by the Navy in 1941, it’s a workaday steel shed that is now home to the Historic Aircraft Restoration Project.

On the morning we visited, Hangar B was full of old planes being lovingly restored by old plane enthusiasts, meaning the volunteers were nearly as historic as the aircraft. The military planes are mostly from WW II and, for a genuine aviation-theme experience, you can climb inside a Lockheed P-2 Neptune retired from the Navy. If you’re not claustrophobic you can crawl forward to the nose of the plane and sit in the gunner turret while your friends take pictures of you.

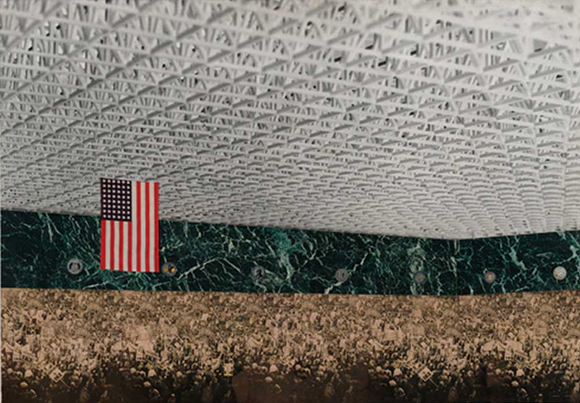

Aside from the planes, the hangar itself is pretty impressive, covering more than two acres and boasting some serious clear spans. With an outsize American flag hanging from the open trusswork, Hangar B reminded me of a famous Mies collage from the 50s, the one with an outsize American flag hanging from the open trusswork.

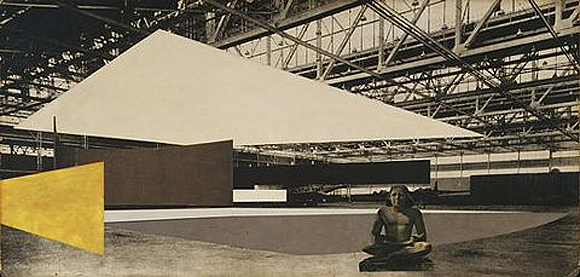

The pure modernism of his 1953 Convention Hall riffed on the borrowed modernism of his 1942 Concert Hall–that one was set in an actual industrial building, designed by Albert Kahn in 1937.

A satisfying historical footnote: the Kahn building Mies’ borrowed for the Concert Hall was an airplane factory nearly contemporary with FBF Hangar B.

In the Mies in America catalogue, Phyllis Lambert notes that, when he was making this collage, Mies used Kahn’s building as a “ready-made structure.” If redeploying an industrial building for a cultural program was mildly shocking at mid-century, it was less so by the century’s end, at least for the sort of people who travel to places like Marfa, North Adams, and Beacon. Visiting the Chinati Foundation or Mass MoCA or Dia and wandering through those enormous ready-made structures filled with enormous modern and contemporary art is sort of like finding yourself inside that Mies Concert Hall collage.

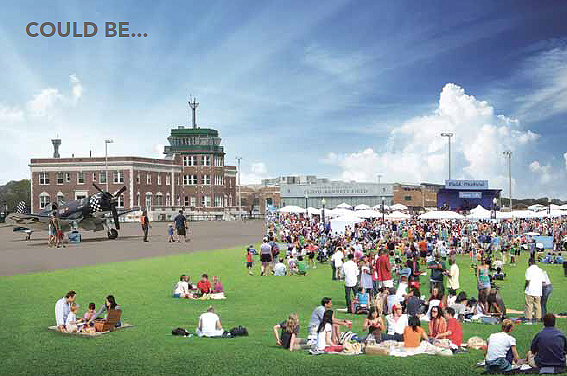

The enormous ready-made structures at Floyd Bennett Field have that same poetic potential. If you can repurpose an artillery shed, a capacitor plant, and a box factory for Judds, LeWitts, and Heizers (and Flavins, Serras, Bourgeoises, etc.), why not an airplane hangar? Why not four airplane hangars?

The ruin porn crowd might prefer to keep them as is, but that’s not going to happen. Last year, a Blue Ribbon Panel–whose members included Christopher Ward of the Port Authority, Robert Yaro of the Regional Plan Association, and landscape architect Diana Balmori–issued a report that described Floyd Bennett Field as “the next jewel in New York’s urban park crown” and called for turning FBF into “an iconic urban national park.” Broken glass and abandonment aren’t really part of the National Park Service aesthetic (to say nothing of Bloomberg’s New York), and the buildings of “Hangar Row” are now destined for “active uses”–whatever that means.

The picnicking New Yorkers in this rendering from the report sure look happy, but pitching a tent by the tarmac isn’t going to be as much fun with all of them around. So book a campsite while the place is still mostly quiet. The urbanism is rough and the nature is ragged, but right now Floyd Bennett Field has a special kind of beauty. And at $20 a night for up to six people, it’s also got the cheapest lodgings to be found in any of the five boroughs.

Flatbush Start to Finish 29 May 2012 No Comments

Stay on Flatbush Avenue long enough in either direction and eventually you hit water, but it wasn’t always like that. One of Brooklyn’s oldest streets, Flatbush Avenue used to be landlocked. In the 17th century it was a country road connecting disparate Dutch farming villages, including Vlacke Bos, from which the avenue takes its name.

In the 18th century, the Flatbush Road was sufficiently improved to require serious defense during the Battle of Long Island (the Americans held the pass against the Hessians thanks to the trunk of an enormous oak, but the British attacked from the rear and the patriots went down in defeat). In the 19th century, under the auspices of the Brooklyn and Flatbush Plank Road Company, it assumed close to its present route, inland through the heart of what was not yet completely the City of Brooklyn (those Dutch villages didn’t allow annexation until around 1895). It was only in the 20th century that Flatbush became the 10-mile long, multi-lane, traffic-choked corridor it is today, its extensions towards the water coinciding two more times with the ambitions of the expanding metropolis.

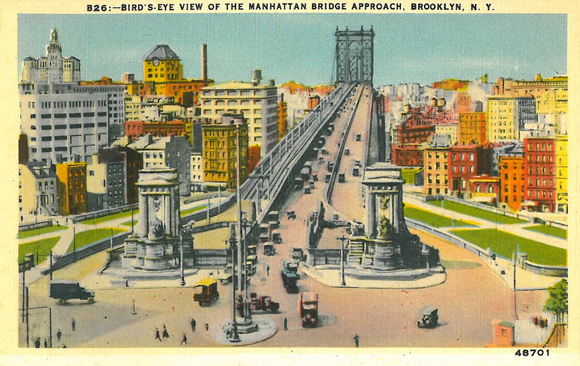

Driving on Flatbush on a typical Saturday night, it can seem as if the only reason they built the segment from Fulton Street to the East River was to accommodate double parking in front of Junior’s. But by the time the cheesecake king open his doors in 1950, this stretch of Flatbush was nearly half a century old, the product of civic boosterism and urban development that typified the decade after consolidation in 1898. The Flatbush Avenue Extension, as it is still called, was completed in 1906 in anticipation of the opening of the Manhattan Bridge a few years later. As originally designed, Flatbush Avenue began at the foot of the bridge, emerging from the upper roadway between two massive granite pylons.

Though not as commanding as the triumphal arched, colonnaded set piece Carrère and Hastings designed for the Manhattan side, their Brooklyn pylons provided the borough’s newest gateway with some serious Beaux-Arts monumentality. At least that’s how it looks in the postcards. Robert Moses demolished the pylons in 1961 during his epic construction of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway.

Among the piles of granite the Powerbroker dismissed as “ornamental masonry” were 12-foot tall allegorical figures of Brooklyn and Manhattan sculpted by Daniel Chester French. After the City Art Commission spared the pair, they moved further down Flatbush and onward to Eastern Parkway, finding a permanent home in front of the Brooklyn Museum.

In substituting highway exit for grand entrance with the callous urban disregard that marked his later career, Moses robbed Flatbush Avenue of a dignified commencement. But three decades earlier, on the opposite side of the borough, at the opposite end of the avenue, Moses achieved the opposite effect, providing Flatbush with a thrilling conclusion.

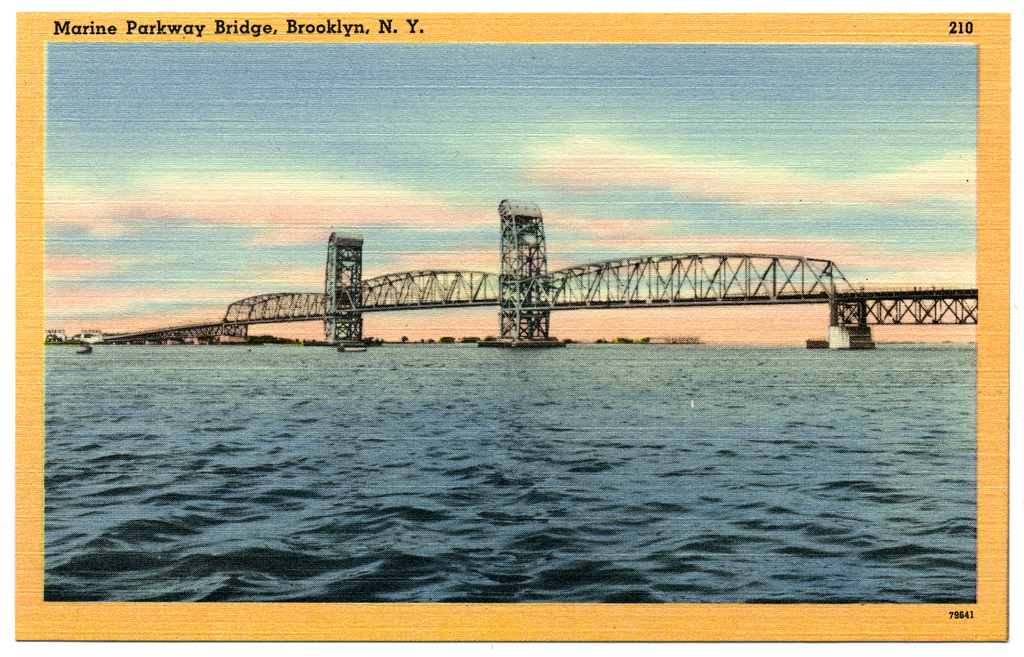

The Marine Parkway Bridge links southern Brooklyn to the Rockaways. The Times declared it a “motorway to seaside” when the bridge opened in 1937, which made sense since Moses built the bridge to to provide car access to the beachfront recreation areas he had just completed at Jacob Riis Park.

Emil Praeger and the firm of Waddell & Hardesty engineered its vertical lift span, the longest in the world at the time. Aymur Embury, the Powerbroker’s favorite architect, designed the towers, terminating them with giant scroll-like forms that house the wheel mechanism in a sort of streamlined combo of classical volute and Chrysler hubcap.

Approached at grade from Flatbush, the bridge really seems like a continuation of the avenue. Past the toll plazas it rises gently over the mudflats and salt marshes. Then, mid-span, above Jamaica Bay, an urban climax: look south beyond the peninsula and you see the Atlantic Ocean; look north beyond the flatlands and you see the skyline of lower Manhattan (Jersey City, too).

If you’re driving it’s hard to appreciate the effect. Better to take to the bridge on foot or bike, which has economic as well as scenic advantages. This being a Moses’ project, the Marine Parkway Bridge was constructed by a public authority, and tolls have been charged from the beginning. Originally, the toll for motorists was 15 cents and back then even the cyclists had to pay. Moses charged them a dime. Today, cars pay $3.25 in each direction, but bikes get to cross for free.

Shop, Dine, Mies 10 May 2012 No Comments

A few weeks ago I had dinner in a strip mall. This is something I do occasionally. Regular readers may recall Two Days in Nevada, in which I recounted having dinner at a Thai restaurant in a strip mall in Las Vegas. This time I had dinner at a Thai restaurant in a strip mall in Detroit.

In Vegas, the restaurant was the attraction; in Detroit the strip mall was the attraction. Anchoring the corner of Lafayette and Orleans Streets on the east side of town, are two one-story retail blocks connected by a small plaza with a parking lot out front. A two-story office block used to occupy the south-east edge of the site; it was torn down a few years ago but its location is still visible in the satellite view.

The Shops at Lafayette Park were built in 1962-63 as part of a large urban renewal scheme that obliterated the old east side neighborhood of Black Bottom, the heart of Detroit’s African American community, replacing it with an interstate and mixed use development. Though a 78-acre site was cleared in the early 1950s, it was not until late in the decade that redevelopment plans were announced.

Eventually–and famously–a dream team from Chicago took over the site: Herb Greenwald as developer, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe as architect, Ludwig Hilberseimer as planner, and Alfred Caldwell as landscape architect. Their superblock scheme included a mix of high-rise apartment towers and low-rise townhouses, along with a variety of community amenities, including a public park, an elementary school, and a shopping center. While the site was not entirely developed according to this plan, the portions that were are now part of the 46-acre Mies van der Rohe Residential District (listed on the National Register in 1996).

The district includes the shopping center; though not designed by Mies, it’s a fine commercial adaptation of his beinahe nichts minimalist approach. Harry King and Maxwell Lewis, the local team responsible for the Shops, employed a compositional modularity and a material palette that echo the nearby towers and houses–covered walkways front open plan retail space, all executed in black painted steel, buff brick, aluminum trim, plate glass. King and Lewis were so pleased with their work here that they moved into the 2nd floor of the office block as soon as it was finished.

Though the 45,000 square foot complex was threatened with demolition in the early oughts, a new owner (First Commercial Realty) renovated the site in 2004 with an eye towards the marketing value of the Shops’ modernist pedigree. (Of course, these are the same owners who tore down one of the center’s original blocks, but never mind.) In addition to refurbishing storefronts and replacing sagging canopies, First Commercial also renovated the pedestrian area connecting the remaining blocks.

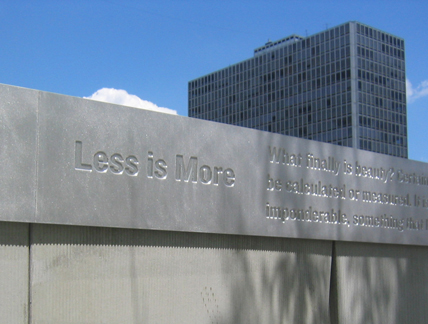

Designed by PLY Architecture and peg office of landscape and architecture, the Mies van der Rohe Plaza is a raised rectangular slab of concrete tiles. Along the edges, these broad tiles are ideal for sitting, but they also deflect asymmetrically from the surface to reveal narrow openings planted with trees and grasses. The slab terminates vertically in an uninspired memorial wall. Typical great man stuff, the aluminum coping is inscribed with Mies’ name, dates, and a few quotes. Predictably, “Less is more” is given pride of place.

I don’t really mind, but it gives the whole plaza an air of taking itself too seriously and, aside from leaving people with the impression that Mies designed the Shops, it threatens to undermine the Gruen-like playfulness of the seating/planting slab. I’m only fussing about the details because there are details to fuss about (“God is in the details,” even if that’s not inscribed on the wall): somebody actually spent the time and money to restore the Shops; somebody thought the residents of Lafayette Park deserved a retail environment as pleasing (and as meticulously maintained) as the rest of the neighborhood.

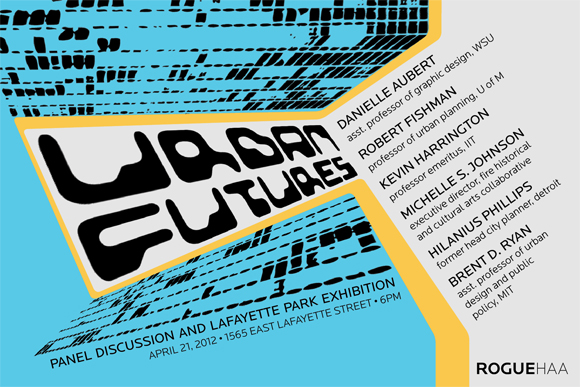

Of course, you can improve the retail space, but that’s not the same thing as improving the retail–especially in Detroit. Indeed, despite the renovation, there is still plenty of vacant space and, thus far, the Shops have been unable to attract the national chains that are typical of this sort of commercial development, and usually necessary to their economic viability. When I stopped by in April, the owners had let a local design group take over prime, un-leased space for an exhibition and other public programs.

RogueHAA is an architecture/urban design collaborative dedicated to generating productive discourse about Detroit’s “urban futures.” At the Shops they installed an exhibition about Lafayette Park’s past and future that gave equal consideration to the Black Bottom neighborhood it replaced and to the folks who live there now, many of whom turned up for a lively panel discussion the night I was there. To advertise events related to “Inside Lafayette Park” RogueHAA installed a large sign just inside the floor-to-ceiling plate glass storefront–a dozen+ florescent tubes spelling out M I E S.

The sign’s combination of Flavinesque simplicity and pop wit was pitch perfect, in a learning from Bob and Denise sort of way. Not sure what Phyllis Lambert thought of it. I heard she came by during the day. The sign definitely looked better at night. In fact, the whole strip mall looks great at night, even the low-rent retail.

Turns out that good design, even when it’s Miesian rather than Mies, can do wonders for a place. In my travels across this vast country, I don’t believe I’ve ever encountered a better looking Dollar General.