Chicks with Bricks 6 June 2013 No Comments

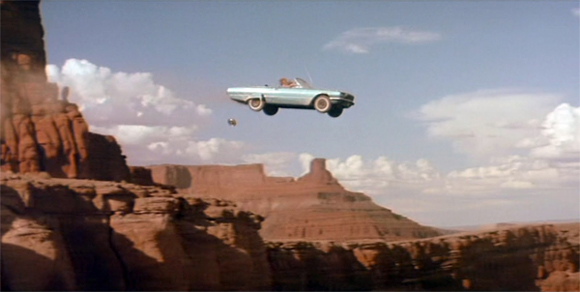

The Thelma and Louise Half-Marathon in Moab is staged in tribute to the 1991 film directed by Ridley Scott, written by Callie Khouri, and shot on location in Southern Utah. The race takes place on the same scenic highway (UT-279) where the eponymous heroines meet their fate after an epic road trip in a 1966 Thunderbird convertible. In the early 90s, the politics of the film, especially in relation to third wave feminism, were complicated, to say the least, but two decades later it’s settled comfortably into iconic status: a gender-bending/genre-blending American classic that’s part western, part road picture, part buddy movie.

The Thelma and Louise Half-Marathon in Moab is staged in tribute to the 1991 film directed by Ridley Scott, written by Callie Khouri, and shot on location in Southern Utah. The race takes place on the same scenic highway (UT-279) where the eponymous heroines meet their fate after an epic road trip in a 1966 Thunderbird convertible. In the early 90s, the politics of the film, especially in relation to third wave feminism, were complicated, to say the least, but two decades later it’s settled comfortably into iconic status: a gender-bending/genre-blending American classic that’s part western, part road picture, part buddy movie.

Which may explain the almost embarrassing euphoria that one still experiences during the film’s chicks-with-guns climax. There may be better movie explosions, but none, to my mind, as satisfying as watching the misogynist trucker get his due.

Running the Thelma and Louise Half, the euphoria is somewhat different (the only gun was the starter pistol), but the sisterly solidarity is just as intense because this is a women’s only race. If you’ve never competed in a road race, you might not understand the appeal of a women’s race. Aside from cleaner porta-potties, a supportive kind of vibe suffuses these events–to such a degree that striving for a personal best starts to seem like a communal goal. Accelerating a few miles from the finish, hoping to come in under two hours, the women running around me whooped and hollered with you-go-girl camaraderie. In the twenty years I’ve been participating in running races, this has only happened when my competitors are all women. And I still get a kick out of it, which is why I’ll keep running in women’s events, whether in canyon country or Central Park.

Back in real life, that kind of women’s camaraderie is just as important, though it can seem harder to find in the male-dominated world of architecture and the academy that I occupy when I’m not on the road. I found it at NJIT when I joined an architecture faculty that included feminist practitioners, thinkers, and historians like Leslie Kanes Weisman, Karen Franck, and Zeynep Celik. I found it at BWAF when I joined a board of trustees and advisors that included equally formidable feminists like Peggy Deamer and Mary McLeod. I found it at Places when I accepted Nancy Levinson’s challenge to contribute to public intellectual discourse about architecture and urbanism–and about women. Places has become an important platform for exploring women’s inclusion and exclusion in architecture, as historical phenomena AND as contemporary polemics, most recently in Despina Stratigakos’ Unforgetting Women Architects: From the Pritzker to Wikipedia, which reminds us of the dangers of cultural erasure and challenges our own complicity in the widespread amnesia about women in design. In the spirit of Thelma and Louise, let’s accept this as a feminist call to arms. But forget chicks with guns; this is about chicks with bricks.

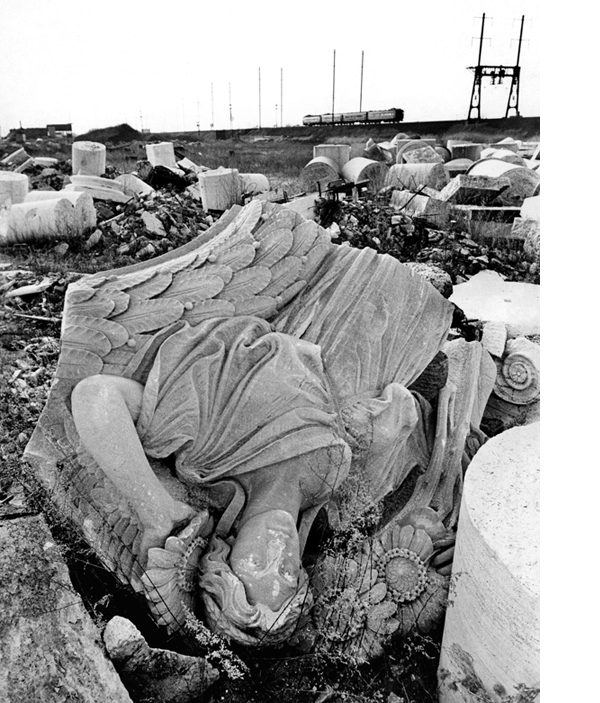

Penn Station, for the record 17 April 2013 No Comments

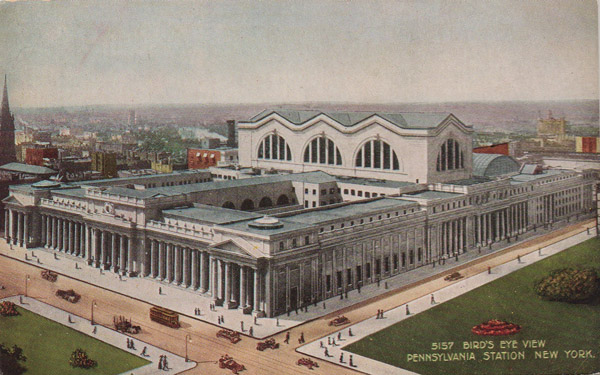

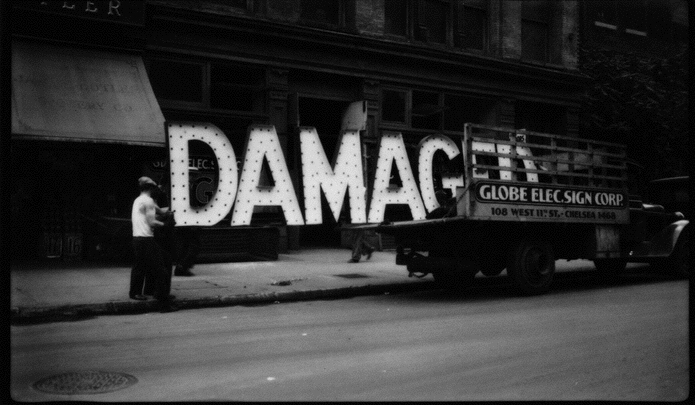

Last week, the New York City Planning Commission held a public hearing to decide the future Pennsylvania Station. At issue, as Michael Kimmelman has explained thoroughly in the New York Times, is whether to allow Madison Square Garden to continue to operate an arena on the site it has occupied since 1968—squarely on top of Pennsylvania Station. My friend and former student, Omar Toro-Vaca (who works for Vishan Chakrabarti and SHoP Architects), urged me to testify at the hearing to add my voice to the public record. Since I was already scheduled to be in Buffalo, attending the annual conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Omar agreed to read this testimony on my behalf.

Chairwoman Burden, Members of the Commission, and Distinguished Guests, my name is Gabrielle Esperdy and I am speaking to you today as a resident of Manhattan, a citizen of the metropolis, and a commuter to New Jersey. In each case, my perspective is colored by my profession: for I am also an architectural and urban historian and a professor of architecture who studies the dynamics of metropolitan transformation in the 20th and 21st centuries by analyzing changing patterns of form and meaning in our buildings and landscapes. As a student of this great city’s past and an active participant in its future, I urge you to deny a renewal in perpetuity of the special permit issued to the Madison Square Garden Company to operate its arena atop Pennsylvania Station.

The Commission has before it a grave decision—it can choose to rectify one of the great tragedies of American urbanism by allowing the redevelopment of Penn Station for this millennium, or it can choose to be on the wrong side of history and allow the nation’s busiest transportation hub to exist as the degraded sub-basement of a venue whose urban presence (regardless of its institutional contribution to the city’s cultural life) bespeaks the outsized mediocrity of an ignoble moment in New York’s past—a moment that far too many people mistook for the twilight of civicism and the fall of the public realm.

The Commission has before it a grave decision—it can choose to rectify one of the great tragedies of American urbanism by allowing the redevelopment of Penn Station for this millennium, or it can choose to be on the wrong side of history and allow the nation’s busiest transportation hub to exist as the degraded sub-basement of a venue whose urban presence (regardless of its institutional contribution to the city’s cultural life) bespeaks the outsized mediocrity of an ignoble moment in New York’s past—a moment that far too many people mistook for the twilight of civicism and the fall of the public realm.

The irony, as we all know, is that the infrastructure of the earlier station is punishingly intact. While it once functioned majestically as what Lewis Mumford called a “gravity flow system,” the gravity doesn’t flow the way it used to—there are simply too many of us now, jammed into concourses and crowded onto platforms that were designed more than a century ago. And while a few of us may smile nostalgically as we descend one of McKim’s original cantilevered staircases down to the tracks, most of us—pressed on all sides by our fellow commuters— are too cranky to notice the vestigial graciousness of this descent, and how different it is from the claustrophobia that typifies track access elsewhere in the station, where we are forced to descend what seem like back office fire stairs rather than grand spaces of intentional circulation. But even if we’ve noticed the difference, we aren’t surprised—because, to paraphrase Vincent Scully, the great Yale historian, we’ve become used to scuttling through Penn Station like a rat.

The irony, as we all know, is that the infrastructure of the earlier station is punishingly intact. While it once functioned majestically as what Lewis Mumford called a “gravity flow system,” the gravity doesn’t flow the way it used to—there are simply too many of us now, jammed into concourses and crowded onto platforms that were designed more than a century ago. And while a few of us may smile nostalgically as we descend one of McKim’s original cantilevered staircases down to the tracks, most of us—pressed on all sides by our fellow commuters— are too cranky to notice the vestigial graciousness of this descent, and how different it is from the claustrophobia that typifies track access elsewhere in the station, where we are forced to descend what seem like back office fire stairs rather than grand spaces of intentional circulation. But even if we’ve noticed the difference, we aren’t surprised—because, to paraphrase Vincent Scully, the great Yale historian, we’ve become used to scuttling through Penn Station like a rat.

I’ve been scuttling like that myself for more than a decade. And in the years I’ve commuted between Penn Station and Newark not once, as I’ve looked out the window on the other side of the Hudson tunnels, have I failed to think about all that fine Tennessee marble sinking deeper and deeper into the muck of the Meadowlands. There is a tendency these days to romanticize ruins, and that’s just fine, as long as they’re not part of your everyday life and your everyday commute. Let me paraphrase Scully again: it’s time we gave all citizens of this metropolis the opportunity to once again enter New York like a god.

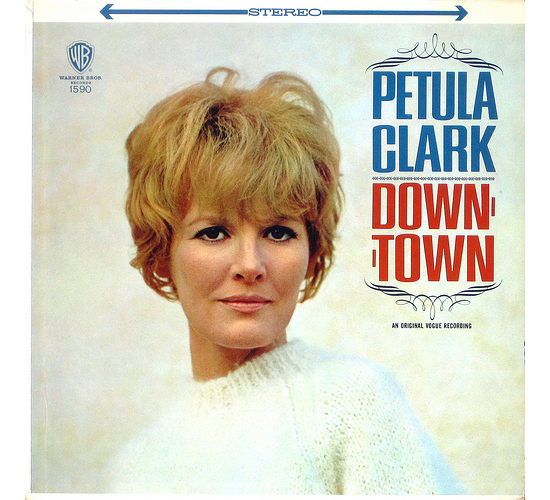

Petula Clark Urbanism 18 February 2013 No Comments

A few nights ago a friend was thumbing through some vintage vinyl at another friend’s house. It’s an eclectic collection of records, the kind you’d expect to find when households merge and roommates depart and children grow up. We’d already heard tracks from Grace Jones, Michael Jackson, and Aretha Franklin, and before the night was through even “The Hustle” ended up on the turntable. We listened to one song after another, from dozens of different records, the order determined by my friend’s whim or the song’s backbeat, until the floor was piled high with messy stacks of covers. If I were pretentious (or still in grad school) I’d say we were musical flâneurs on a Top 40 dérive, but in the days before we knew how to shuffle our playlists, I used to call this “rambling DJ,” and that pretty much says the same thing–wandering with no other aim than listening pleasure.

Eventually, our DJ rambled us back to December 1964 when Petula Clark’s Downtown was released in the U.S. We played it once and then we played it again, and as I sat there listening to that analogue recording on a cold winter’s night in a house very far uptown, it was like hearing Downtown for the very first time. And what really struck me was the silky optimism of Tony Hatch’s lyrics. Based, supposedly, on a recent trip to New York, the song offers traffic, neon, and noise as balm for the soul. But in the mid-60s, there were plenty of people who regarded those same urban effects as generators of blight, the kind of urban that was desperately in need of renewal. Though The Death and Life of Great American Cities had been around for a few years, and had already been called “significant” (by the New York Times, no less), it hadn’t spent 15 weeks at the top of the charts the way Clark’s single did. I’m not yet prepared to offer a theory of causality between the success of downtown, the song, and the rebirth of downtown, the place, but I’m working on it–because there’s a larger narrative here about the relationship of pop culture to urban discourse that is well-worth exploring. In the meantime, if anyone knows whether or not Jane Jacobs was in the audience for Petula Clark’s first American nightclub appearance, at Copacabana in October 1965, I’d be happy to receive the information.

Prelude: May 2006 1 February 2013 No Comments

What follows is probably too autobiographical, and certainly more bloggy than usual for this blog, but I hate to waste a piece of perfectly good writing–good, not necessarily in terms of quality, but meaning a text already written, never distributed, hanging out in an obscure file folder taking up space (if 105KB counts as taking up space). And good, too, in the way it anticipates what would become American Road Trip. Reading the text now, almost seven years after it was written, I’m struck by the degree to which ubiquitous mobile technology has changed the way we see, experience, and remember the world we encounter in our everyday lives. Perhaps that’s a banal observation in this iPhone era, but banalities intrigue me as much as extraordinaries, and that’s kind of the purpose of what I’m trying to do here on this site.

[NB: as will be clear below, I didn’t have a camera; all images used under Creative Commons license.]

Walking up Sixth Avenue on a nearly perfect spring morning, my friend and I were headed to the Donald Judd show at Christies, but we were talking about the Guggenheim.

She observed that maybe Wright’s spiral worked pretty well after all: at least for monographic shows (David Smith: a Centennial had just closed), the unwinding layers give you an almost archeological view of an artist’s work, allowing you to probe/glance backwards and forwards in time and space as you look across the rotunda at the various “strata” on display.

I shifted the conversation to the building’s exterior and asked if she had noticed the mistake on the façade, now in plain sight because of the current renovation. With layers of paint and concrete removed one can see that the craftsman carving the letters on the façade had initially started too high up, rather than at the lower edge as Wright had specified in his drawings.

Thus, the “T” generally visible in “The” has a ghost just above it—somewhere between a palimpsest and a pentimento, I suppose—bearing witness to fact that the building was made by hand (and thus subject to human error), despite the machinist precision of its forms.

I told my friend that I wanted to take a picture of the ghost letter, but that I keep forgetting. She observed that there are often things she sees on the street that she wishes she could record in some way in order to use them at a later date. We talked about the value of having a camera in one’s mobile phone to be used for such a purpose.

I mentioned that I had been inspired to start walking around with a camera after seeing a Walker Evans show at the Met some years ago, but this had not amounted to anything. She talked about what she might do with such images once she had them collected, perhaps assemble them in some accessible way and then use them as a reference point or inspiration. A thing glanced in the physical world becomes a memory connected to its original experience; almost simultaneously, it becomes an image to be deployed, perhaps in an entirely different context, perhaps entirely disassociated from the original experience. My friend is an architect and a designer; she might use the thing-memory-image in a formal exploration of color or texture or scale, contrasted or juxtaposed, for a project on paper or realized in built form. But I am a historian and a writer. How will I use the thing-memory-image?

Here is a clue. My friend lent me a book called Chasing the Perfect by Natalia Ilyin; I took copious notes. Among the many things the book made me realize (too many to mention here) is that in pursuing my chosen profession—getting the Ph.D., getting the tenure-track job, getting tenure—I have too often forgotten my vocation. I have forgotten what propelled me into architecture in the first place—not the practice of architectural design (I bailed from my first and only architecture studio after four weeks), but the practice of architectural writing. Now, I spend a good deal of my time outside of the classroom engaged in architectural writing, but I’m talking about real pleasure-of-the-text writing, writing that isn’t intended for a peer-reviewed journal or an academic press, writing that explores an idea for its own sake without concern for the validity of an argument or the burden of evidence. And this is where the thing-memory-image comes in: having collected these for as many of my forty years as I can remember, I have yet to make use of them in my practice. What follows is my first attempt to write into that void.

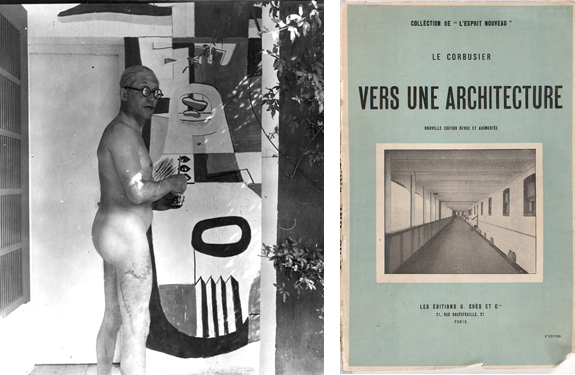

Here is another clue (or maybe a rationalization of recurring feelings of inadequacy at being an architecture professor who doesn’t teach design). Le Corbusier pursued a double métier (painting + architecture) his entire life, but given his corpus of written work, it might be more accurate to say he pursued a triple métier. For Rem, research, writing and design are parallel tracks of his architectural practice (hence OMA spawned AMO). What follows, then, is writing towards architecture and writing as architecture. Hopefully, it is the first of many minor texts to come.

Darkness on the Edge of Town 3 November 2012 No Comments

The darkness wasn’t confined to the edge of town, but there was something startling about seeing it there, at the edge of the island, on the bikeway, in the gloaming. North of 34th Street the lights were on; south of 34th Street they weren’t. At twilight you could still make out the distinctive profile of the darkened street lamps, teardrop luminaires hanging from mast-arm poles (replicas of a 1908 design), stretching down the length of the West Side Highway.

A bit later, and a mile or so inland, where the street wall tends to obscure the sky, the transition from light to dark was more dramatic. Riding down Lower Fifth toward what the wags had already dubbed “SoPo”–as in South of Power–I kept thinking of a scene in The Chronicles of Narnia (Book 3). As the Dawn Treader sails closer and closer to a dark and looming mist, the brightness gives way to grey and then “beyond that again, utter blackness as if they had come to the edge of a moonless and starless night.” In Manhattan, this occurred somewhere below 23rd Street where the car headlights and the pedestrian flashlights created long, wavy streaks, colored arcs against a black background.

Pausing to look back north to where the power was still on, the Empire State Building, framed by so much darkness, seemed taller than usual. Its setbacks lit up in orange and white, the tower was surprisingly reassuring–in that way you suddenly appreciate something you normally take for granted.

Pausing to look back north to where the power was still on, the Empire State Building, framed by so much darkness, seemed taller than usual. Its setbacks lit up in orange and white, the tower was surprisingly reassuring–in that way you suddenly appreciate something you normally take for granted.

I’ll admit to taking the building’s changing color scheme for granted: red, white, and blue for July 4th, etc. I wrongly assumed the orange lights were for Halloween, but they were actually meant to draw attention to the “after Sandy” relief efforts of the Food Bank for New York City.

Turning from the tower to the street, it took a while for your eyes to adjust to the darkness. Eventually, about the same time you realized how pathetically dim your bike headlamp really was, the buildings slowly emerged from the gloom, and you could make out the apartments, the offices, the stores. Here, a really long exposure captures a blank wall and a water tower against the lightless skyline.

Turning from the tower to the street, it took a while for your eyes to adjust to the darkness. Eventually, about the same time you realized how pathetically dim your bike headlamp really was, the buildings slowly emerged from the gloom, and you could make out the apartments, the offices, the stores. Here, a really long exposure captures a blank wall and a water tower against the lightless skyline.

Further downtown, the dark was darkest on the side streets where the traffic and ambient illumination were almost nonexistent. Off Varick Street, close to the Holland Tunnel, which was still closed because of flooding, the high-rise commercial lofts give way to a few isolated blocks of low-rise residences. In row after row, there were no candles flickering, there were no devices glowing. I leaned my bike against a gate and snapped a few pictures. They looked pitch black, but upping the brightness and contrast later on revealed what registered on the camera’s sensors that night: a late federal town house where the windows were as dark and mute as the frames were ghostly and white. Either no one was at home, or they’d all turned in early. I knocked a few times, but the rapping seemed indecent on such a silent street, so I got back on my bike and pedaled home.

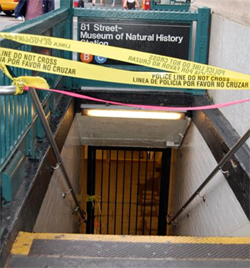

Uptown things were different. Unless you went looking for them, the downed tree limbs in the parks and the river silt washed up by the surge were easy to miss. Walking on Central Park West or Broadway towards the end of the week, only the subway entrances–with old school yellow police tape or info-age electronic services advisories–hinted at the devastation elsewhere.

Uptown things were different. Unless you went looking for them, the downed tree limbs in the parks and the river silt washed up by the surge were easy to miss. Walking on Central Park West or Broadway towards the end of the week, only the subway entrances–with old school yellow police tape or info-age electronic services advisories–hinted at the devastation elsewhere.

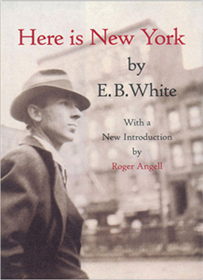

At times like these in the city, one turns, inevitably, to E.B. White: “New York is peculiarly constructed to absorb almost anything that comes along…without inflicting the event on its inhabitants so that every event is, in a sense, optional, and the inhabitant is in the happy position of being able to chose his spectacle and so conserve his soul.” In this case E.B. didn’t get it quite right: no one in the unhappy position of living in Lower Manhattan or the Rockaways or Staten Island was choosing his or her spectacle. Elsewhere in the five boroughs you knew what he meant: life went on for the rest of the eight million, at least until they had to get to work.

At times like these in the city, one turns, inevitably, to E.B. White: “New York is peculiarly constructed to absorb almost anything that comes along…without inflicting the event on its inhabitants so that every event is, in a sense, optional, and the inhabitant is in the happy position of being able to chose his spectacle and so conserve his soul.” In this case E.B. didn’t get it quite right: no one in the unhappy position of living in Lower Manhattan or the Rockaways or Staten Island was choosing his or her spectacle. Elsewhere in the five boroughs you knew what he meant: life went on for the rest of the eight million, at least until they had to get to work.

Reading Here is New York is generally balm for the soul, but this week it was strangely discomforting, and White’s celebration of the city’s “patience and grit” did little to relieve the queasiness brought on by observations like this: “By rights New York should have destroyed itself long ago, from panic or fire or rioting or failure of some vital supply line in its circulatory system or from some deep labyrinthine short circuit…It should have been overwhelmed by the sea that licks at it on every side.”

Post-storm, it is prudent to stay with the essay all the way to the end because there, in the last few paragraphs, White brings you back around. He doesn’t finish on a particularly happy note: writing in 1949, with WWII still fresh in his memory, White identifies a subtle change in the city–the recognition that New York is destructible. “The intimation of mortality is part of New York now,” he wrote then, in a simple sentence that still resonates a half century on. White didn’t lament this new reality, and neither should we. Instead, he seized it as an opportunity to reflect upon the city’s value to him individually, and to the culture as a whole. New York, White concludes, is a “mischievous and marvelous monument which not to look upon would be like death.” Riding through the darkness as the city regained its bearings, I knew exactly what he meant.